| ||||

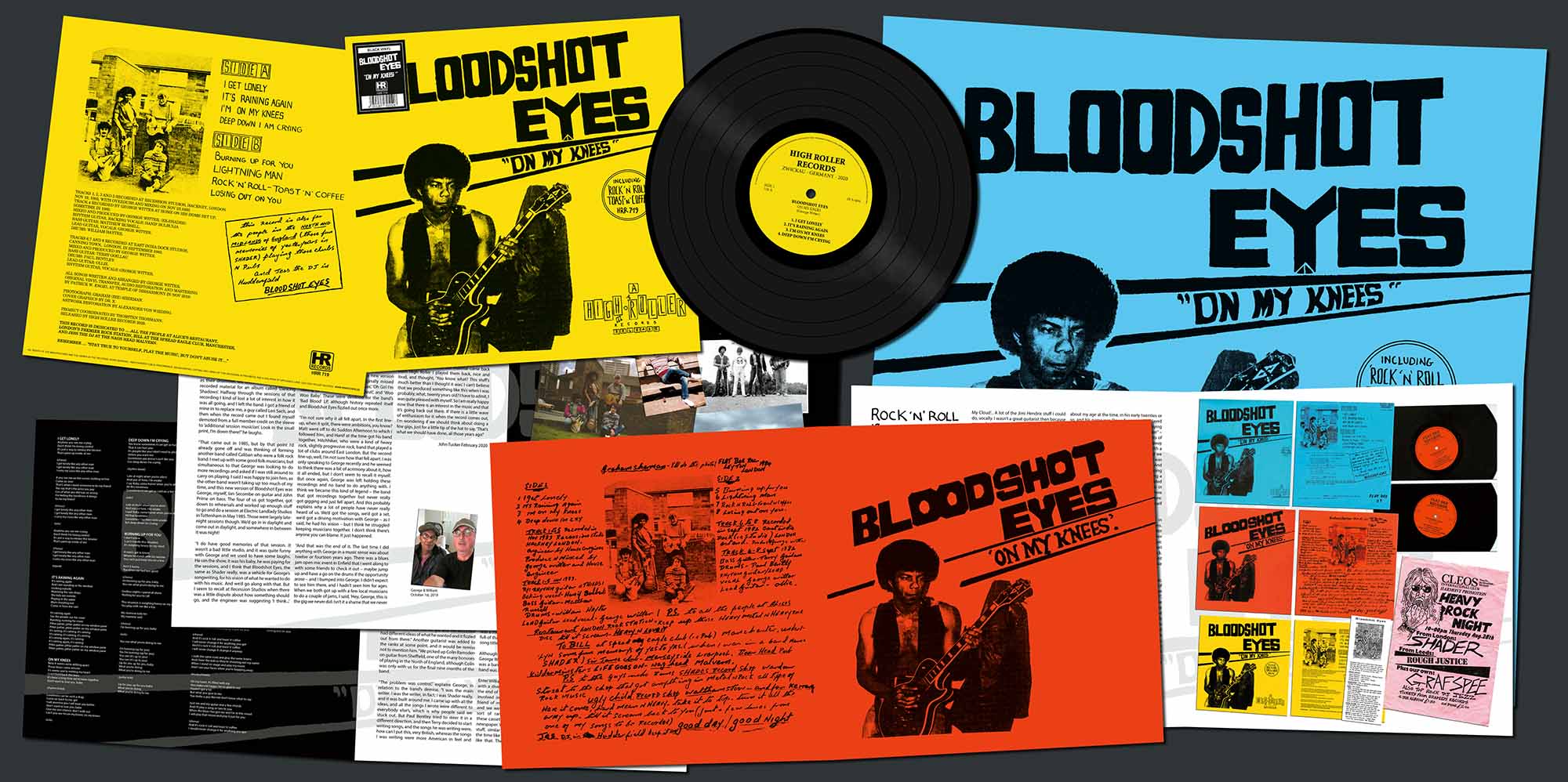

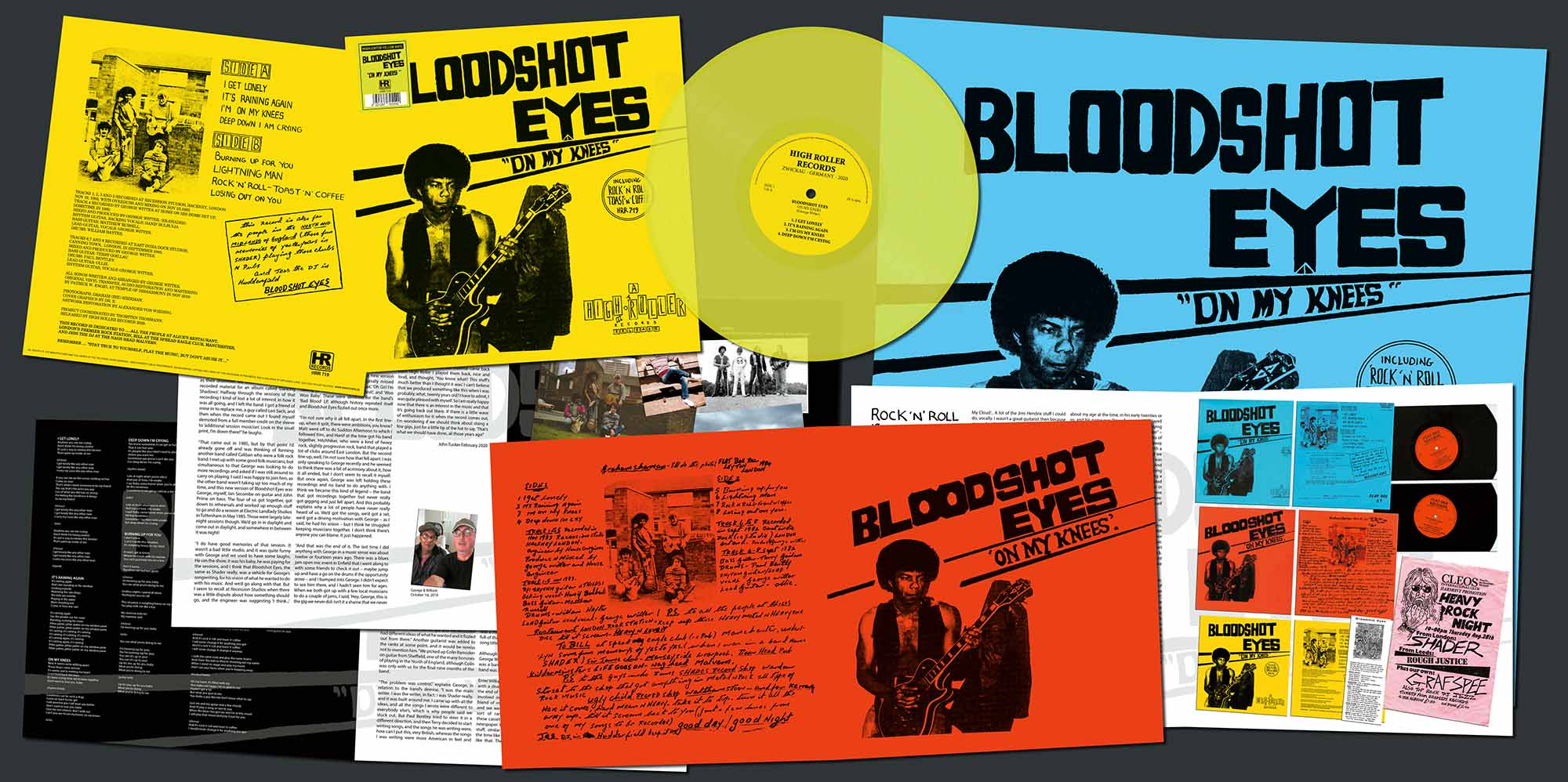

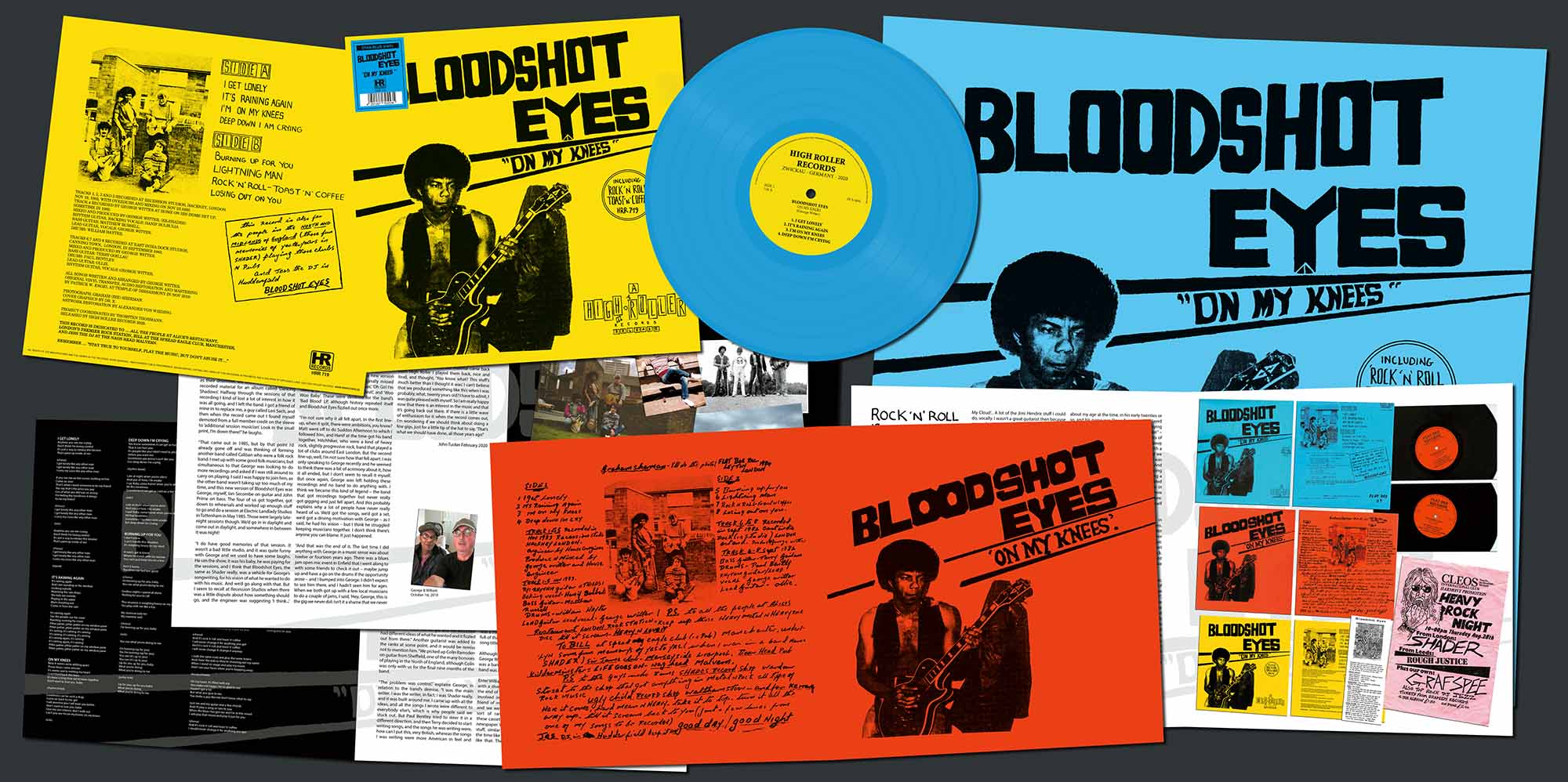

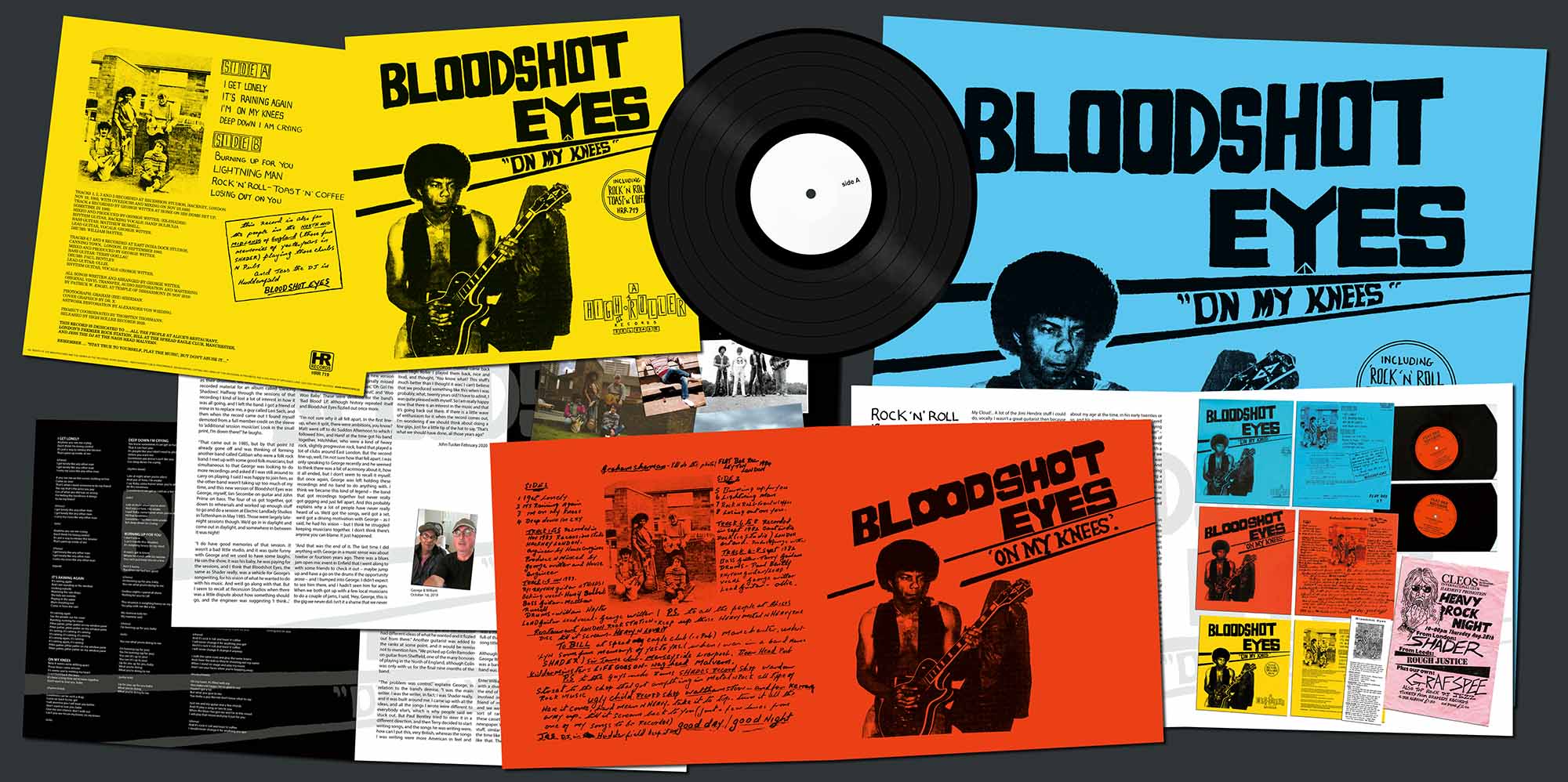

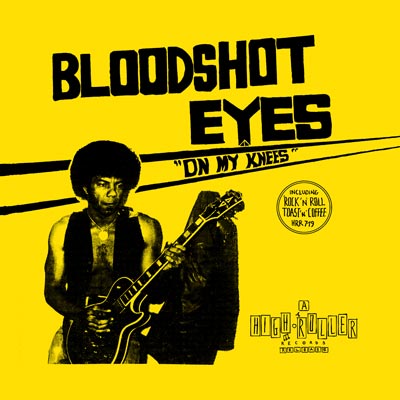

| BLOODSHOT EYES - On My Knees LP | |

HRR 719, ltd 300, 100 x black, 100 x transparent highlighter yellow, 100 x cyan blue vinyl, 8 page booklet, poster | |

| Tracks 1-5 George Witter - vocals, lead guitar Hanif Balbulia - rhythm guitar Matthew Russell - bass William Hayter - drums | Tracks 6-8 George Witter - vocals, rhythm guitar Ollie - lead guitar Terry Goillau - bass Paul Bentley - drums |

| 01 I Get Lonely 02 It's Raining Again 03 I'm On My Knees 04 Deep Down I Am Crying 05 Burning Up For You 06 Lightning Man 07 Rock'n'Roll - Toast'n'Coffee 08 Losing Out On You | |

SOLD OUT! | |

audio restoration and mastering by Patrick W. Engel at TEMPLE OF DISHARMONY in November 2019

“ROCK ‘N’ ROLL IS FULL OF MISSED OPPORTUNITIES...”

Time tells no lies, Praying Mantis famously once said, but it certainly dims the memory. Shader’s George Witter and Bloodshot Eyes’ William Hayter piece together the conjoined history of the two bands.

Known for just one single, 1981’s ‘Bad News Blues’, Shader were a hard-working London-based band, fronted by the charismatic George Witter, who paid their dues and had what it took, but just never got lucky.

Their story begins when the teenage George arrived in the UK to join his parents. “I’m a Caribbean guy,” he begins. “I came here in ’67 to join my parents. I was 16 at the time and I was used to listening to reggae back home, well, it was more ska then. I got off the plane, and it was freezing cold,” he laughs. “I thought, ‘my God, I didn’t realise there was snow!’ Anyway, I started hearing some of the British pop music at the time which was bands like The Who, The Stones, The Move, and that was really groovy. I really was intrigued by that kind of stuff. And then, by the end of the summer I heard Jimi Hendrix, saw him on TV and thought ‘Oh, black man on TV’. That’s what went through my head. ‘I want to do that.’

“I had polio, so I wound up with a hip problem. So walking was a bit of a problem from the age of ten – I had to learn to walk again. I couldn’t play sports, but the guitar intrigued me, after seeing a few people on TV; that and the British pop music really intrigued me. I wanted to learn how to play guitar but I never really started till I was about nineteen. I started going down to the local bars and the local pubs round my area – I lived in North London at the time, so places like Walthamstow – and I used to watch guys on stage and think, ‘I wish I could do that’. Anyway, I started to learn a few little songs on guitar and I found some songs I really could sing like ‘Stand By Me’, ‘Get Off Of My Cloud’... A lot of the Jimi Hendrix stuff I could do, vocally. I wasn’t a great guitarist then because remember I started late, but gradually I started jamming with a few people – getting up on the jam nights – and then a few guys approached me and said ‘Hey, come and try out for our band’ as a singer. I wanted to be a guitar player. That’s what I wanted to be, a bloody guitar player!” he laughs. “But they liked the tone of my voice. My voice has dropped now but back then I could hit some keys, you know? But unfortunately I didn’t have enough experience to carry the tunes which need timing. One guy did tell me straight – and we became great friends; we’re still friends now – he said to me ‘George, you’ve got a great voice, great tone, great everything, but you’ve got to go away, sit down and get your timing and sort of really apply your mind to it.’ And that’s the best piece of advice anyone ever gave me.

“Eventually, I started jamming around my area, and I wound up playing with a few guys in a garage over in North Chingford. The first band out of that would have been about ’74, something like that, and the band was called Ginger Zulu.” Another laugh. “We had this girl who used to hang around – a lot of the local kids, sixteen-, seventeen-year-olds would hear us jamming and come in – but this girl had ginger hair and amazingly we liked the word ‘ginger’ but we didn’t know what to put with it. And there was that big movie, ‘Zulu’, with Michael Caine, so when one of us said ‘Ginger...’ someone else said ‘...Zulu’ to make it some kind of exotic thing.

“After that, though, I just drifted around, really, and just played. I became a bit of a local celeb because of my voice, really. People loved the tone of my voice. So I used to get to jam with a lot of people, and that really helped me. And then the next band after Ginger Zulu was Shader, which was formed in the summer of 1976. I met Richard [Wright – guitars"> and he had a mate called Terry Goillau who wanted to play bass, but we didn’t have a drummer. We always had a problem finding drummers.

“There was a band around Walthamstow called Sam Apple Pie – Sam Sampson’s band –and they had a few records out and I remember going to a gig down in Walthamstow, seeing the band and then winding up meeting his brother who was about my age at the time, in his early twenties or so, and his name was Doug Sampson. He played with us and, guess what, he ended up playing in an early version of Iron Maiden. But Shader” – the story behind the name is lost in the mists of time, unfortunately – “we’d keep banging away in the old garage there and we came up with a few songs, macho things like ‘The Pimp’, and we had a song called ‘The Jungle’ and the jungle was basically about how tough it was out there. And then we had this other song called ‘Lightning Man’, about rocking out down the pub, having a good time, trying to get a few ladies. We ended up playing in Alan Gordon’s rehearsal studio in Walthamstow. Desolation Angels rehearsed there was well, and they were the loudest band in there. You’re in there, but you can’t even hear yourself because they were so fucking loud.”

Shader played everywhere and anywhere in London, including the legendary Ruskin Arms. “Iron Maiden had a good long spell there. Shader used to play there the Thursday night – we never made it to the Friday or Saturday! And the music we were doing wasn’t heavy-heavy... It was sort of rock, progressive rock as well, and blues rock. We weren’t really out-and-out heavy. I didn’t want to do that type of thing because everybody else seemed to be doing it.”

By this time, the band had a permanent drummer, Paul Bentley, who’d signed up in the spring of 1978, and with a settled line-up and a growing fan base, Shader decided to issue a self-financed 7”. ‘Bad News Blues’ b/w ‘Banging Like A Shit House Door’ appeared in 1981 on their own Piston Broke Records. “‘Bad News Blues’ was a new song and we decided to go with something fresh,” recalls George, “and ‘...Shit House Door’ was always towards the end of our second set of the night and it was very popular so we decided to put it on the B-side of the single. It was a lot heavier onstage, and it was a real classic – all the guys seemed to love that one, just the phrasing. And it’s a good old English saying, as well, isn’t it!” A third track, ‘The Pimp’ was also meant to be on the record, but George can’t recall now why that didn’t happen.

“We called the label Piston Broke, we had an image of a piston and it was broken, but we were always pissed and broke. That was the joke. There wasn’t a lot of money in it, but it was enjoyable. But we found out we were making more headway going up north so we’d wind up playing in Huddersfield, Wakefield, Manchester, Ashton under Lyme, all that area, we used to go up there quite a lot – go away on the Friday and come back Sunday evening so we could all get to work before we chucked our jobs in and went for it. We played with a lot of northern bands, second on the bill to them, and we had some great times. And as we had no accommodation, they’d usually let us sleep in the pub. We had sleeping bags. We had a big van kitted out, but when it got really cold they’d let us sleep in the pub. We’d gradually get to know the locals, get invited to parties and have somewhere to crash. It was great; really, really good fun. We had to give it a shot, and spent about three, three-and-a-half years at it. It was great finding out that fans in the North really loved us. We didn’t have a great hold on the scene in London, we had about six pubs we’d play quite regularly where we did quite well, but the North really did love us.”

A further demo followed in September 1982, recorded at East India Dock Studios, and featured three new songs: ‘Lightning Man’, ‘Rock ‘N’ Roll – Toast ‘N’ Coffee’ and ‘Losing Out On You’. Some major label showcases were also arranged, but, predictably, the dice didn’t fall in Shader’s favour. “We had this local guy who decided to be our manager,” says George, “and he got us three showcases for labels. Polydor came, Decca came, I can’t remember the other one, but Polydor was the one who was going to give us that shot. But then that A&R man was let go, and his successor had different ideas of what he wanted and it fizzled out from there.” Another guitarist was added to the ranks at some point, and it would be remiss not to mention him. “We picked up Colin Ramsden on guitar from Sheffield, one of the many bonuses of playing in the North of England, although Colin was only with us for the final nine months of the band.

“The problem was control,” explains George, in relation to the band’s demise. “I was the main writer. I was the writer, in fact; I was Shader really, and it was built around me. I came up with all the ideas, and all the songs I wrote were different to everybody else’s, which is why people said we stuck out. But Paul Bentley tried to steer it in a different direction, and then Terry decided to start writing songs, and the songs he was writing were, how can I put this, very British, whereas the songs I was writing were more American in feel and suited the way I used to sing. So I’m telling them, ‘Look, if we change this we change the band, you know?’ So we started going that way and I decided I wasn’t going to sit there and let somebody, well, not tell me what I should do, but if we changed our direction when we’d got a good direction going on and it was getting better, it would just set us back. People seemed to like the way I was doing it, and as we broke up a label in Wolverhampton wanted to put us on a compilation with ‘Rock ‘N’ Roll – Toast ‘N’ Coffee’ and ‘Lightning Man’. But because we broke up there was no band to do gigs.

“I think we were mentally strained with each other. They said that’s the song that got away because ‘Rock ‘N’ Roll – Toast ‘N’ Coffee’ was a very popular song and even now today I play it on jam sessions and people say ‘Oh, you should record that.’ I did record it!” he laughs. “It’s a crazy life, isn’t it! And the thing about ‘Rock ‘N’ Roll – Toast ‘N’ Coffee’ is that it does tell the story as to how you feel as a musician - just me and my guitar and a few chords. That’s how I felt at the time, and the lyrics just came straight out of my head.

“We had some good times in Shader, and I’ll tell you now that it’s a really good feeling to know that I did something, off my own back, many years ago, that people are interested in now. That does make me feel good inside. And had we been on that compilation, alongside some of the real upcoming New Wave Of British Heavy Metal bands... Well, it was a missed opportunity really, but rock ‘n’ roll is full of that, isn’t it. Actually, that would be a good song title...”

---

Although Shader were now officially defunct, George Whitter was still full of ideas: all he needed was a band to get them down on tape. And that band was Bloodshot Eyes.

Enter William Hayter, a drummer and percussionist with a diverse range of musical interests, who at the end of the Seventies was, as he puts it, “Very involved in the independent cassette scene. A friend of mine was running Conventional Tapes and we were doing a lot of improvised music, sort of random free-form stuff, and getting these cassettes out that were selling via Sounds newspaper. We never gigged it, but just recorded stuff, similar to the German-sounding music at the time like Can and all the experimental bands like that. Then, when that finished, I recorded some stuff for the Whaam! label (run by Dan Treacy of Television Personalities) with Tangerine Experience, which came out on a compilation release, ‘All For Art...And Art For All!’

“So,” he continues, “at the time I was experimenting with quite a few musician friends, and line-ups changed on an almost weekly basis. We’d go to rehearsal rooms and be jamming and rehearsing and whatnot. And then I met up with George, by mutual friendships, really. There were local pubs, music pubs and venues, and it was a case that everyone knew everyone, and George was part of that crowd. He had this track history of rock music, and I do remember going to see Shader at Bridge House in Canning Town one time. Anyway, Shader had kind of ground to a halt, and, although I can’t remember now how Bloodshot Eyes came together, me, George, Hanif [Bulbulia – rhythm guitars"> and Matthew [Russell - bass"> started doing rehearsals with some new songs that George had written. When we’d got them rehearsed up well enough we went into the studios, Recession Studios in Hackney, to record them.” This was in November 1983, and the songs the band put to tape were ‘I Get Lonely’, ‘It’s Raining Again’, ‘I’m On My Knees’, ‘Deep Down I’m Crying’ and ‘Burning Up For You’.”

The band’s name came from the assembled musicians being a little too worse for wear. “There were times when we’d drink too much, a little puff or two too many... We’d usually end up around someone’s house and get roundly trounced, and if you listen to the recordings, I realise now that I got the beat completely wrong in places and wonder what kind of a state I was in when I recorded it!”

Despite having a demo tape, though, nothing really seemed to happen next. “I’m not entirely sure why we didn’t end up taking it around and start gigging,” says William now. “I think the idea was to try and get a recording ready first, then get rehearsed up ready for our first gig. So, once we’d got these recordings done, George compiled them with some old recordings from the Shader years” – the September 1982 tape – “and there was enough there to make an LP, ‘On My Knees’. George, on his own decision, got them all pressed up on vinyl, along with these home-made sleeves, if you want to call them that. Not dissimilar to the independent stuff I’d been doing, but this time it was on vinyl rather than cassette. George then got busy with selling the records, he got mail order set up, put adverts in the music papers, and I think with his history with Shader he still had a reputation so there were some fans who were like, ‘Oh good, there’s something available’, and were buying it. Largely we left it all to George to deal with that sort of thing. But we didn’t do any gigs with this line-up and then suddenly it all sort of wobbled and fell apart, and George was left on his own with the records. This would have been about ’84. At that point Matthew left and joined a band called Sudden Afternoon, who were on the Midnight Music record label, and I followed him as their drummer. We went into the studio, and recorded material for an album called ‘Dancing Shadows’. Halfway through the sessions of that recording I kind of lost a lot of interest in how it was all going, and I left the band. I got a friend of mine in to replace me, a guy called Len Sach, and then when the record came out I found myself demoted from a full member credit on the sleeve to ‘additional session musician’. Look in the small print, I’m down there!” he laughs.

“That came out in 1985, but by that point I’d already gone off and was thinking of forming another band called Caliban who were a folk rock band. I met up with some good folk musicians, but simultaneous to that George was looking to do more recordings and asked if I was still around to carry on playing. I said I was happy to join him, as the other band wasn’t taking up too much of my time, and this new version of Bloodshot Eyes was George, myself, Ian Secombe on guitar and John Prime on bass. The four of us got together, got down to rehearsals and worked up enough stuff to go and do a session at Electric Landlady Studios in Tottenham in May 1985. Those were largely late-night sessions though. We’d go in in daylight and come out in daylight, and somewhere in between it was night!

“I do have good memories of that session. It wasn’t a bad little studio, and it was quite funny with George and we used to have some laughs. He ran the show, it was his baby, he was paying for the sessions, and I think that Bloodshot Eyes, the same as Shader really, was a vehicle for George’s songwriting, for his vision of what he wanted to do with his music. And we’d go along with that. But I seem to recall at Recession Studios when there was a little dispute about how something should go, and the engineer was suggesting ‘I think...’ blah-blah-blah... ‘it should go this way,’ George stopped him and said, ‘I’m paying the bill here, I’m paying the money, you do what I tell you’!” William laughs at the memory. “And of course the rest of us are rolling about with laughter! George has a very direct point of view and we all loved him – we did then and we do now – but once he’s got his mind set on something, that’s the way we’re going. But that said, if it wasn’t for his ideas and his vision, I don’t think any of this would have happened.”

Six songs came from that session: a new version of ‘The Pimp’ – the song that originally missed the Shader single – ‘Foot On The Gas’, ‘Oh Girl I’m Talking To You’, ‘Bad Blood’, ‘The Devil’, and ‘Woo Woo Baby’. These were destined for the band’s ‘Bad Blood’ LP, although history repeated itself and Bloodshot Eyes fizzled out once more.

“I’m not sure why it all fell apart. In the first line-up, when it split, there were ambitions, you know? Matt went off to do Sudden Afternoon to which I followed him, and Hanif at the time got his band together, Hitchhiker, who were a kind of heavy rock, slightly progressive rock, band that played a lot of clubs around East London. But the second line-up, well, I’m not sure how that fell apart. I was only speaking to George recently and he seemed to think there was a bit of acrimony about it, how it all ended, but I don’t seem to recall it myself. But once again, George was left holding these recordings and no band to do anything with. I think we became this kind of legend – the band that got recordings together but never really got gigging and just fell apart. And this probably explains why a lot of people have never really heard of us. We’d got the songs, we’d got a set, we’d got a driving motivation with George – as I said, he had his vision – but I think he struggled keeping musicians together. I don’t think there’s anyone you can blame. It just happened.

“And that was the end of it. The last time I did anything with George in a music sense was about twelve or fourteen years ago. There was a blues jam open mic event in Enfield that I went along to with some friends to check it out – maybe jump up and have a go on the drums if the opportunity arose – and I bumped into George. I didn’t expect to see him there, and I hadn’t seen him for ages. When we both got up with a few local musicians to do a couple of jams, I said, ‘Hey, George, this is the gig we never did. Isn’t it a shame that we never managed to hold it together enough to get out and do this back then...’”

Like many other musicians from the NWOBHM, William was “blissfully unaware” as to how collectible bands like Shader and Bloodshot Eyes have become. “Since I’ve realised that there’s an interest in this music, I’ve kind of revisited it and given it a good listen,” he says. “And when the remastered WAV files of our material came back from High Roller I played them back, nice and loud, and thought, ‘You know what? This stuff’s much better than I thought it was.’ I can’t believe that we produced something like this when I was probably, what, twenty years old? I have to admit, I was quite pleased with myself. So I am really happy now that there is an interest in the music and that it’s going back out there. If there is a little wave of enthusiasm for it when the record comes out, I’m wondering if we should think about doing a few gigs, just for a little tip of the hat to say, ‘That’s what we should have done, all those years ago’.”

John Tucker February 2020