| ||||

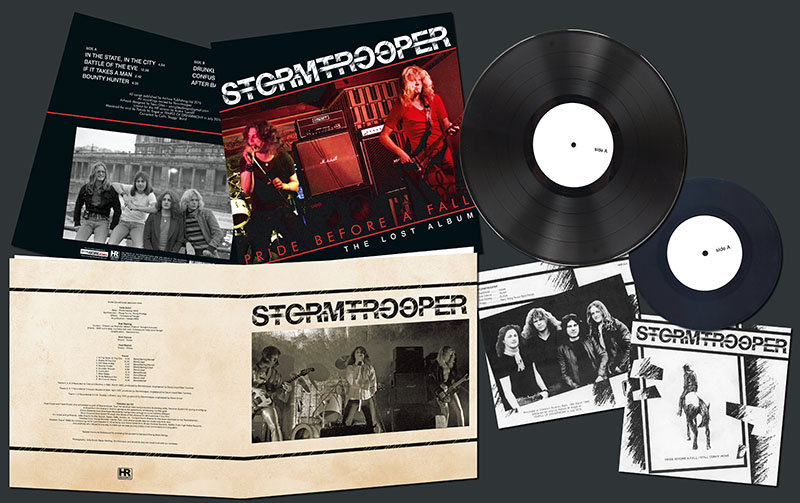

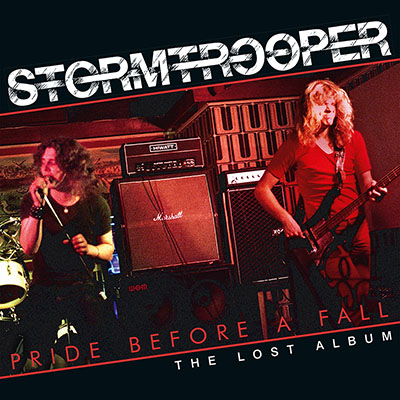

| STORMTROOPER - Pride Before a Fall (The Lost Album) LP+7 | |

HRR 524, ltd 500, 200 x black + 300 x transparent blood-red vinyl, bonus 7" in p/s | |

| Paul Merrell - Vocals Bob Starling – Guitars Colin Bond - Bass Nick Hancox - Drums | |

| 01 In the State of the City 02 Battle of the Eve 03 If It Takes A Man 04 Bounty Hunter 05 Drunken Woman 06 Confusion 07 After Battle 08 Pride Before a Fall 09 Still Comin' Home | |

SOLD OUT! | |

BONDED BY BLOOD…

There was no great exodus in the glory days of the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal of Bristol-based bands to London, which is a great shame as like, say Jaguar and Shiva, Stormtrooper would almost certainly have had a better shot at beating the odds had they upped sticks and moved to the Capital. Founder member Colin ‘Boggy’ Bond recalls the struggles of being in a band who refused to conform and who lived beyond the glare of the media spotlight.

We all did it, back in those pre-internet days. Whereas booking arena tickets nowadays is a matter of sitting at your PC and clicking refresh every ten seconds, back in the dark ages the only guarantee of success was to queue outside the venue or ticket outlet and to hope your luck held by the time you’d finally reached the front of the line. For that very reason schoolboys Colin ‘Boggy’ Bond and Stephen ‘Squib’ Webb spent an uncomfortable night outside Virgin Records in Bristol, hoping to get tickets for Led Zeppelin’s 1975 Earl’s Court shows. Under-dressed and unprepared for their ordeal Bond and Webb finally engaged the person next to them in conversation, at the same time as helping him dispose of his sandwiches and coffee. His name was Robert Starling and the hapless pair were enthralled to discover that he not only had a Gibson Firebird, but that he could actually play it; “unlike me and Squib with our respective instruments – bass and drums – that we’d only bought a few weeks earlier,” laughs Bond. “We were in need of a proper guitarist with a proper guitar, so after we had recovered from the night’s ordeal Bob made the first of many trips across Bristol from Kingswood to Hartcliffe, where we lived.” At that time Hartcliffe was one of the most deprived estates in the country, a place where less than a month earlier Bond and Webb “had been set upon by a gang just for having long hair, and which a few years later would make world news as the place that provided the spark to ignite the Bristol riots which would eventually spread to the rest of the country.” The nascent line-up seemed to gel though. “After we bluffed our way through a couple of rehearsals with Bob he agreed to join our school band Digby Weed, a group of Hartcliffe's finest with their eyes set firmly on the future.”

By Christmas 1975 Digby Weed played its third and final gig in a rather run-down sixth-form common room at school, with vocals provided by Nigel Lloyd. “That was a vast improvement on our previous outings,” recalls Bond. “We’d only been playing a few short months but we were doing all the rock classics and were finding it easy. Unfortunately the disco-loving sixth formers we played to saw us as no more than an irritation.

“By this time I had already seen Led Zeppelin at Earl’s Court, had broken into the Colston Hall for a second night to witness Ronnie Montrose and Sammy Hagar smash main act Status Quo out of the ball park, and been suspended from school for a week after bunking off to see Grand Funk Railroad at Wembley Empire Pool. I was being driven by another force. I didn’t want to be a grown-up living in the real world. I wanted to be the best bass player in the world; I wanted to be a bloody rock star! My school friends moved on to follow their dreams of domestic bliss and I left school not wanting to commit to any career so I found myself in the farcical situation of finding it difficult to get an ordinary job as I had too many qualifications, so I signed on the dole. Bob was already a fully-qualified electrician when we met him and although he was also driven by his deep passion for music, he had ‘options’. He was also responsible for introducing drummer Frank Powell to the band. The quartet was now complete: we had a band, a van, and our sights set on world domination.” What they didn’t have, though, was a name.

“This was before ‘Star Wars’ so that had no bearing on our decision, but we all had ideas of what the name should be; so in the end we wrote several names on pieces of paper, screwed them up, put them in an ashtray – we were in a burger bar at the time – and drew out the name. I can’t remember who thought of Stormtrooper, it might even have been me, but now I don’t think any of us really knows for sure.” And although they weren’t the only band to use the name, Bond is quick to point out that “only with the advent of the internet did I become aware of other Stormtroopers. I saw a review recently that said ‘Stormtrooper, not to be confused with that superb rock band from Bristol’ and I was chuffed when I read that.”

There’s little doubting the band’s dedication and enthusiasm at this time. “We rehearsed every Saturday morning in a church hall whether we had a gig or not. And in the early days gigs were few and far between. Rehearsing was a long, drawn-out affair for Bob as he was the only one who could drive and so ferried everybody about, and criss-crossing Bristol four times every Saturday after a hard week’s work must have taken it out of him. But we enjoyed rehearsing just as much as gigging – it was all just one big adventure. Like most young bands we drew on our musical influences which varied dramatically between the four of us and provided hours of heated discussions as there were few bands that proved to be a common denominator, but Led Zeppelin and Rush were always at the front of our minds. We quickly started to introduce original material into the obligatory two hour rock covers’ set we’d put together and gained a reputation for not only playing our own material, but also for the covers played with our own arrangements and distinctive style. In the summer of 1976 this resulted in a residency at one of Bristol’s top pub venues The Naval Volunteer, a place always full and bristling with musicians. Nervous System were one of the few Bristol bands we had a lot of time for, a great bunch of musicians and the band responsible for giving us, earlier that year, our first bit of exposure at ‘The Volley’ by letting me and Bob do a few songs with them when things were quiet. I suppose we were unintentionally networking, as it’s called these days, although unfortunately our networking skills left a lot to be desired and we tended to ‘say it as we saw it’.”

1976 is renowned in the UK for its long hot summer, a rarity in this part of the world. It was, of course, also the year in which punk began to rear its noisy head. “One thing we could never understand was the thriving new wave scene in Bristol. It seemed like a good excuse for poor musicians to parade their inept, amateurish material to shallow like-minded punters and promoters. I always thought music was about musicians and musicianship but with the coming of punk and new wave I began to have my doubts. After hearing one particularly poor band (and bass playing display) by supposedly one of Bristol’s finest at The Volley I was told in no uncertain terms that this guy had ‘probably forgotten more than you know’. I squared up and retorted ‘he’s forgotten fucking everything!’ We never deliberately went out of our way to alienate Stormtrooper within the local music fraternity and we were very polite and diplomatic most of the time but, unfortunately, always honest.” The band were now also making regular visits to the many other music venues in and around Bristol at that time, which eventually led them to achieving the first of their many goals: on 10 November 1976 they played the Granary, the most legendary of Bristol’s venues, four days after the Scorpions’ second visit. “Life,” says Bond simply about this period of the band, “was fun.”

With things going so well, it was inevitable that something had to give. “Frank was a solid drummer and the nicest bloke you could meet, but he got married and joined the domesticated career-minded home-owner set. We had a short stint with another drummer until we encountered Nick Hancox at a gig early in 1978. Telling us that our new drummer was shit compared to him and that we’d be a much better band with him in it he appeared to be a man after my own heart, so we decided to give him a try.” Described by Bond as “arrogant, cocksure, witty, intelligent and a fantastic drummer,” Hancox was not only exactly the man Stormtrooper needed, but in addition he was the perfect partner to Bond’s way of playing and writing; someone who, in Bond’s words, could help “elevate my bass playing skills to another level; someone who understood and could play with ease complicated time signatures, syncopated rhythms and dovetail perfectly with my bass style. We now had a powerhouse rhythm section to die for. We could hold our own with anybody in the world and our music started to get more and more technical with the introduction of longer, complex arrangements. There were no restraints on what we did or what direction we wanted to go in, so I pushed everything to the limit in terms of performance and composition.

“By late 1978 our set comprised mostly our own material with the odd favourite thrown in here and there if needed. It was at this time we took our first tentative steps into a recording studio, the fruits of that endeavour having long since disappeared. It was the first time the Moog Taurus pedal synthesiser was introduced to the band, a tool that enabled me to play counter melodies on bass whilst playing the lower-end passages on the Moog (or vice versa). Later, a Moog Prodigy keyboard was also added which gave further options. The only thing wrong with the Taurus was that it wasn’t particularly user-friendly and bending down mid-gig to adjust the variable settings wasn’t an option. Basically, I had one pre-set and one pre-mixed signature voice that I used throughout – and probably overused at times,” he laughs.

The opportunity to release a single came via Simon Edwards and his local Heartbeat Records. It was Edwards who suggested Crescent Studios in Bath to the band, and in March 1980 they recorded four songs in one session. However, even that was fraught with difficulty, given that just before the session the band parted company with Nigel Lloyd. “We were changing rapidly both musically and visually and felt the days were gone when it was cool to stand on stage supping bottles of Guinness in your day clothes, something we’d all been doing just a few months earlier! Nigel was never comfortable with the idea of wearing stage gear; in fact, his exact words, which I’ve never forgotten as it was all I could do to keep myself from laughing whilst trying very hard to be serious for a change, were ‘I ain’t dressing up like a fuckin’ Christmas tree for no c*nt’. He also understandably disliked – as Paul would come to do – prolonged bouts of standing around on stage while the rest of us ‘did our thing’; but when he refused point blank to help fund studio time it caused an impasse that we were not going to resolve. We recruited Paul Merrell, another Hartcliffe lad we’d known for some time – the brother of a mate of ours with no previous track record – and his first job was to come up with the words to ‘Still Comin’ Home’, a song that was finished but for the lyrics.

“Although heavy rock wasn’t Heartbeat’s thing, and Simon knew very little of the genre, he was obviously impressed with our attitude, enthusiasm and not least our talent, and maybe thought it was a market he could tap into. Two songs from that first session at Crescent, ‘Pride Before A Fall’ and the now completed ‘Still Comin' Home’ stood out as a potential single. They were the most commercial of the four tracks we’d recorded and were an obvious choice. It’s a double-A-side single as we couldn’t make up our minds which was the best of the two at the time: I personally always preferred ‘Still Comin’ Home’ but I've got so used to people over the years referring to it as the ‘Pride…’ single that it’s pretty much become the A-side now.”

Within a few months of the session Stormtrooper had their first record out. Bond reckons that the pressing was about 3,000 copies. “It was a great feeling. I went for a pint with Nigel some time later and although he hadn’t sung on it he had the single framed and proudly displayed on his living room wall. Well, it did have his name on it, after all.”

Lloyd’s pride was nothing though compared to how Bond felt a few weeks later when he returned to the building site where he was working, clutching the latest copy of Sounds. Leafing through the pages he was amazed to see ‘Pride Before A Fall’ at No.23 in the paper’s heavy metal chart. “I jumped up and punched the air, much to the surprise of everyone else in the tea hut,” he recalls. We’d done this without a manager or any kind of promotion. Several years after Stormtrooper’s demise, I found out that we actually did impress a number of musicians in the rock world, Joe Elliot and Bruce Dickinson to name but two. We were making waves but knew nothing of that at the time. Bugger!” he laughs. “There we were, stuck in Bristol, not realising that the record was going down well at rock venues up and down the country. And of course we couldn’t capitalise on a situation we knew nothing about. Eventually we managed to get the odd gig in London, Manchester and Cardiff and always went down well, but Bristol was our comfort zone. We’d set up a rota system with all the available venues locally but we really needed to break that circle, and that’s something we never really achieved.”

The band taped a second session at Crescent in April 1981, where the three epics ‘Battle Of The Eve’, ‘Confusion’ and ‘After Battle’ were recorded, and would then follow it up with a shorter two-song stint at S.A.M. Studios in Bristol three months later. “I can remember the look on the engineer’s face at the second Crescent session when we told him we were now going to record four tracks in one morning. And then when we said that three of them were twelve, ten and eight minutes long he just laughed and said ‘well, let's do one and see if we have time left’. We recorded the three songs here in pretty much the time it took to play them, and then with a few minutes left on the clock did a version of ‘If It Takes A Man A Week To Walk A Fortnight Then How Long Is A Piece Of String’.

Asked what song or songs best represent Stormtrooper, Bond pauses for a moment. “The rest of the band may have their own preferences, and it is difficult to choose just one or two songs from the album as I honestly believe they are all brilliant in their own way even though they may not be executed as crisply as I would have liked because of time and financial restraints. Given a week to record those songs and not just a day and a half, the album would be legendary – mind you, it’s not far off now.” Another laugh. “But I adore ‘Confusion’ because it’s clever, aggressive, ambient, different, and more than anything breaks the mould. Because every passage is subtly different in timing to the last it’s not until you try to work it out that you realise how much has gone into it, both in terms of composition and performance. It has no guitar solo, unthinkable in a rock song, it has no chorus, unthinkable in a rock song, and it has a wonderful atmospheric drop down middle eight section which makes me want to dive into the speakers and swim around in its ambiance. It has a vibrancy and urgency that other bands can only dream of capturing. It’s in your face and won’t let up.

“It was a first take, recorded in eight minutes, totally live with nothing added or taken away. Not a crappy twin lead guitar solo, big operatic yodelling lead vocal or tacky predictable anthemic chorus in sight. Probably my downfall, actually,” he adds with irony, “as the band eventually wanted crappy twin lead guitar, operatic vocals and anthemic choruses!

“I really don’t care if people didn’t or don’t understand it. It would be nice if they did. But that's not the point. It wasn’t a conscious experiment of mine. It was organic in its evolution, and it was a natural progression to me. It was an attack on the senses, it shouted ‘we’re good and don’t we know it!’ This was our sound and this is what we sounded like live on stage, as is the case with all the other tracks on the album. We made a lot of noise for three blokes and a singer! For me, it’s Stormtrooper through and through, and I love that song with a passion!

“By now, our recordings collectively had now grown into an album,” says Bond, going back to the April 1981 session at Crescent. “We wanted to record some of the longer tracks so we could provide a good cross-section of our work. But although they were impressed, this second visit to Crescent didn’t provide Heartbeat with any single material, and they weren’t interested in doing albums at that time. And it’s a great shame they didn’t hear the S.A.M studio recording of ‘In The State In The City’ later as that would have made a really good follow-up single to ‘Pride…’.”

Despite that burst of impetus that ‘Pride Before A Fall’ had given the band, as 1981 rolled on it was apparent that Stormtrooper had plateaued. “We were all very, very good musicians, and as a rhythm section there was no-one out there at that time Nick and I feared; we could more than hold our own with anybody,” says Bond with some pride. “Looking back we did overplay a bit, but that’s all part of Stormtrooper’s charm. Bob adapted well to anything we threw at him. I loved his tight riffing, guitar sound, and some of those crackly, noisy analogue pedals he used brought his rich bluesy solos to life. Paul was good with lyrics, as was Nigel. He had a good studio voice and always delivered when interpreting the compositions he was given. We were tight as a band, arrogant, defensive and protective.

“And thanks to the NWOBHM rock music had had a bit of a renaissance,” he continues, “and bands like Iron Maiden and Saxon were even appearing on ‘Top Of The Pops’. We were on a bit of a high after releasing our first single and some successful gigs including a support slot to Spider – who we blew off stage – at the Music Machine in London. But things had started to go a bit flat. Even local bands Jaguar and Lautrec with Reuben and Laurence Archer were making inroads, the latter driven by Reuben who was pretty shrewd and business-minded and who managed to secure a British tour as support to Saxon. To my mind, these bands were OK but I felt not in our league. It was our passion for music that drove us, not being business minded, and with us still trying to hold down day jobs it started to become apparent that we needed something other than talent to get on.” Certainly, the band needed management, and had they had the wherewithal to move to London things might have happened for them. But they were in the classic musical chicken-and-egg situation: they needed to move to London to make contacts and raise their profile, but they needed to make contacts and raise their profile to move to London. As a result, or maybe as a symptom, cracks began to appear in the band’s line-up.

“The way I remember it, Paul was becoming a bit of a ‘rock star’, not carrying his fair share of equipment, not buying rounds, never ready when being picked up to go to gigs (pissing ‘the chauffeur’ – Bob – off no end). Nick had a couple of ‘unfortunate’ incidents: ripping a light bulb out of its socket in a dressing room at a gig and then soldiering on with a swollen, blistered and cut right hand didn’t help the cause; and falling off his drum stool at the Granary ‘for some reason’ left us rather embarrassed and asking the audience ‘is there a drummer in the house?’ Luckily a guy called Eddie Parsons was on hand to finish the set; he was a bloody good drummer, and a bloody good job he did, too. Bob was getting a little moody and I was getting a little dictatorial: I fully believed in what we were doing, what I was writing and how we sounded. Absolutely nothing could dissuade me from that. But for a band who were feeling the pressure all these trivial episodes collectively were magnified.

“Paul had a good voice but was rather inconsistent at times. Unlike Nigel, he was having to write melodies and lyrics over finished pieces of music in keys he probably wouldn't have chosen for himself. As a result of that and the deafening volume we played at his pitching suffered at times. I knew he wasn’t happy with hanging around doing nothing on stage for long periods and I think he became a little indifferent. He was very upset when we parted company,” Bond recalls, but that was just the prelude to what was to come. “Not only had Nick apparently developed an overnight dislike of my bass playing, as I had developed a dislike of his apathy and destructive nature, but Nigel, only back in a temporary capacity for a few weeks, had suggested that the band undergo a radical change of direction.

“Nigel admits that hindsight is a wonderful thing but says that he remembers that at the time the bottom seemed to have dropped out of what he called ‘intelligent’ rock in favour of the more commercial and easily accessible singalongs of the likes of Def Leppard, Kiss, Iron Maiden etc. He only told me recently that Bob was chatting to someone at The Target Club in Reading, where he was asked if we were a heavy metal band. Bob replied, ‘yes, we are, but as soon as you start headbanging we’ll change the time signature’ which made Nigel think ‘maybe that's the problem; perhaps we’re being a bit too clever and leaving the audience behind.’ To me, our diversity, individually and collectively, was our strength and that’s what made us stand out from the crowd. What we desperately needed was management, but the rest of the band seemed to think that ‘dumbing down’ was the answer and that this would make us more acceptable.”

‘Dumbing down’? “I wouldn’t like to upset any NWOBHM or metal fans in general, but I never considered us falling into either of those categories. People try to pigeonhole Stormtrooper, but it’s quite impossible. If we followed one path only it would have been a little easier, but I personally was happy with our varied, evolving output. When we started in 1976 we were old school heavy rock, and ended up involved in a period that was labelled the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal. I feel it did a lot of other bands a disservice, being dragged into that ‘club’, because the vast majority of the plethora of heavy metal bands around at that time were crap,” he says, with alarming honesty. “They were full of enthusiasm but crap all the same! I hardly ever listened to it then and I never listen to it now. It just left me cold most of the time. I like all sorts of music (my favourite band was and still is Wang Chung, power pop/rock) but the predictable riffs, song structures and technical ability of the likes of Iron Maiden, Judas Priest and Saxon just didn’t impress me at all. There you go, that’s really alienated me now!” he laughs.

“A few journalists lately have said we were influenced by Iron Maiden which is far from the truth: there’s no way we’d taken anything from them. You must remember that Stormtrooper were finished by the end of August 1981 when the likes of Iron Maiden and Def Leppard were really still in the infancy, in terms of what they would go on to achieve. I’d never really heard any Iron Maiden – I don’t think any of us had – until I saw them on ‘Top Of The Pops’ when I moved to London after we’d split.

“So when they said they wanted us to be what I saw as just another one of those run-of-the-mill NWOBHM acts just to get a foothold, and I was told to modify my bass playing and writing, I reacted. It wasn't going to happen. I was never one for the safe option – push it and see where it takes you, and if it falls apart (and sometimes it did) then so be it. Looking back from now, life is one big compromise at times and in most cases for the better, but a headstrong arrogant kid may have other ideas, and ‘be different or don’t bother’ was my motto. People liken us to Rush and Zeppelin, which I suppose is quite flattering in one way, but there is not a lick, riff or phrase anywhere on this album that has been directly lifted. You listen to your peers and it obviously has an influence on your output, but your individual style should bleed through too. There were several exciting new songs that sounded more Stormtrooper than anything else that was written in 1980/1981 which were due to be recorded at our next studio outing. And what you have here, like most albums, is just a soundbite of what we were about; you needed to come to a show to see how all this stuff, and the stuff that didn’t make it to the studio, worked in its entirety.”

The inability to find a way through this stand-off was the end of the band. Starling and Hancox would make one more trip to the studio, recording three songs with Paul Guesting on vocals and Merv Woolford (co-owner of S.A.M. Studios) on bass. “There were some promising moments,” says Bond, “and Merv’s bass playing was good. But for me the spark was missing, that spark you get when the sum is better than its individual parts.” The songs recorded on the day were ‘Keep On Going’, ‘Here We Are’ and ‘Something’s Wrong’, but according to Bond, “Bob doesn’t consider this as Stormtrooper, and to be honest the session really has nothing to do with Stormtrooper and sounds nothing like Stormtrooper. Stormtrooper” he adds, “was not whole, and would never be again.”

Meanwhile, Bond was now unemployed – musically, at least – and needing an outlet for his creativity he answered the ‘Wanted Bass Player (Name Band Split)’ advert in Sounds. “When Stormtrooper fell apart, I felt completely alienated. There was no point staying in that upsetting environment, and within two weeks I’d auditioned for a new band. Shortly afterwards I gave up my day job and moved to London – this would have been October 1981 – where, funnily enough, I joined the remnants of Bristol band Lautrec, vocalist Reuben and his step-son guitarist Laurence Archer, to form Stampede. I was so arrogant I felt I could walk into any band but I was surprised to find that out of the seventy or so bass players who auditioned I had only just made it, and one of the reasons against me was that I was Bristolian! It wasn’t until I moved to London that I came to understand the scale of ridicule, venom and distrust levelled at people from Bristol, and ‘if you go down well in Bristol you'll go down well anywhere’ was a phrase I heard time and again. This was a eureka moment for me though, and made me realise that it wasn’t the fact Stormtrooper weren't good enough – something I never believed anyway, but which had niggled away at me from time to time – but the fact we were from Bristol.

“By Christmas we’d already written a set which contained the likes of ‘Hurricane Town’, ‘Movin’ On’, ‘Missing You’, ‘The Other Side’ and ‘Photographs’; there’s a showcase we did in January 1982 which I have a recording of and which contains all of these songs. [Bond is justifiably proud of the fact that, backstage at a Sammy Hagar gig, Joe Elliot told him that ‘Photographs’ had inspired ‘Photograph’, the song which marked Def Leppard’s return to the UK Singles chart for the first time in three years."> By March amongst others ‘Days Of Wine And Roses’ and ‘Shadows Of The Night’ had joined the list. But shortly afterwards, prior to signing with Polydor, a huge rift formed within the band. Alan [Nelson – keyboards"> left, Frank {Noon – drums"> was sacked, and, unusually for me, I decided to keep my head down as I wasn't ready to move back to Bristol. But that incident and the break-up of a very enthusiastic, productive, talented bunch of musicians all pulling in the same direction showed me there was a lot more to the music business I needed to learn about – but that’s another story!

“I primed Nick Hancox for the vacancy behind the drum kit and he told me he was keen,” recalls Bond.“On my recommendation the rest of the band were ready to have him on board. But he changed his mind overnight, adding fuel to the fire regarding Bristolians and their apathy. The rest of the band just glared at me and the manager grabbed the phone and gave Nick a piece of his mind before Nick put the phone down. I tentatively said with a whisper ‘I do know another good drummer…’” Now living in London, trying to forge a career in music, Eddie Parsons from Bristol band Stargazer, the man who’d saved Stormtrooper’s bacon by standing in for Hancox a few months earlier when he’d ‘fallen off his stool’, was now asked to join Stampede. “And what a fantastic job he made of it.”

Meanwhile, in April 1982, at roughly the same time as Stampede were honing their act in London, Jaguar, now with Paul Merrell on vocals, were in Wallsend recording their ‘Axe Crazy’ single for Neat Records, and in doing so opened the door for the speed metal boom to follow. “Over the following ten years I visited Bristol only occasionally,” says Bond, “and was never aware of what was happening with the music scene there. Paul had joined Jaguar and I did get them a support at the Marquee for Stampede, but this was the only time I came in contact with their music. Nick, who was a massive Lone Star fan (as we all were), joined forces with Kenny Driscoll and played on and off with him for several years; he also had a stint with Bronz. Nigel went back to his blues/folk roots and joined several bands with similar interests. Bob kept his hand in and played with various musicians in Bristol before forming Hunted a few years later. After Stampede had fallen out of love with Polydor, I played with a myriad of world famous musicians. I toured and recorded with Bernie Tormé. I was asked by their management to audition for Status Quo, which I refused. Then Arista Records invited me to do a European tour with Meat Loaf, which I accepted. Ex-White Spirit and Gillan guitarist Janick Gers and I put a band together for a short period with Frank Noon on drums and White Spirit’s Malcolm Pearson on keyboards, but that never really got off the ground. My lovely Bristolian wife was now working for CBS records in London, but after our first child was born she wanted to move ‘back home’ so I put my Bristolian hat back on and packed my suitcases. Janick of course joined another mate of ours, Bruce Dickinson, for his early solo stint and then followed him back to Iron Maiden when Adrian Smith left. As for me, after we moved back to Bristol, although I continued o play bass in many top West Country acts, I never played professionally again.

“When I heard the restored and remastered tapes for the first time, after all these years, it was like listening to somebody else. I could totally detach myself from Stormtrooper and listen to it as a punter would listen to it. And you know what? I thought ‘what a fucking brilliant band that is!’”

John Tucker September 2016

Credits etc by Colin Bond

At the Stormtrooper sessions were:

Colin Bond

Bass – Rickenbacker 4000

Synthesisers – Moog Taurus, Moog Prodigy

Effects – Colorsound Flanger

Amplification – Hiwatt/WEM

Bob Starling

Guitars – Gibson Les Paul SG, Gibson Firebird. Yamaha Acoustic

Effects – MXR micro amp, cry baby wah wah, Colorsound Delay and Flanger

Amplification – Marshall/Vox

Nick Hancox

Drums – Sonar

Paul Merrell

Vocals – Shure

Tracks

1. Pride Before A Fall 3.01 Bond/Lloyd

2. Battle Of The Eve 12.38 Bond/Lloyd

3. In The State In The City 4.57 Bond/Starling/Merrell

4. If It Takes A Man A Week To Walk A Fortnight Then How Long Is A Piece Of String

2.44 Bond/Starling/Merrell

5. Bounty Hunter 4.01 Bond/Starling/Lloyd

6. Still Comin' Home 4.30 Bond/Merrell

7. Drunken Women 5.59 Bond/Lloyd

8. Confusion 8.16 Bond/Merrell

9. After Battle 9.42 Bond/Merrell

Tracks 1, 5, 6, 7 Recorded at Crescent Studios in Bath, March 1980; produced by Stormtrooper, engineered by David Lloyd/Glen Tommey

Tracks 2, 8, 9 Recorded at Crescent Studios in Bath, April 1981; produced by Stormtrooper, engineered by David Lloyd/Glen Tommey

Tracks 3, 4 Recorded at S.A.M. Studios in Bristol, July 1981; produced by Stormtrooper, engineered by Steve Street

THANKS GO TO

Nigel Lloyd and Frank Powell who will always be part of Stormtrooper. ‘Gus’ for his short lived but productive drumming skills. Nervous System for giving us a leg up. Al Reed from the Granary Club for giving us the opportunity of realising our first goal. Simon Edwards from Heartbeat Records for being brave enough to try something different. Brian Coombs from Bristol Musical, the centre of the universe for all musicians in the 70's. Our wives and girlfriends, Julia (thanks for the Taurus), Karen, Sally, Sandie, Jo. Richard Harris (thanks for the down payment on my Rickenbacker). Roadies Dave ‘Honey Monster’ Clarke, Trev, John and anybody else we could rope in to help. Stephen 'Squib' Webb for introducing me to ‘Led Zeppelin II’. Mike Darby and Steve Street from Bristol Archive Records, Steffen from High Roller Records, and anybody who helped in any way to make our six-year journey a little more comfortable and enjoyable.

Special thanks to Rotosound for providing the wonderful Standard Swing Bass Strings

Photography: Julia Bond, Karen Starling, Stormtrooper and anybody else we could trust with our cameras.

Track Notes

There were several songs that didn’t make it to the studio sessions for one reason or another. Funds were limited so we chose material we felt would best further our aim to secure a recording contract although none of them would have been out of place in this collection. I’m sure the period live recordings we have and recent re-recordings we’ve made of these songs will become available at some stage.

Crescent Studios in Bath was a place we knew nothing of until recommended to us by Simon Edwards of Heartbeat Records. They were used to dealing with bands such as XTC and musicians like Peter Gabriel and heavy rock was a medium they’d never worked with before, but we were impressed with the care and attention to detail they lavished upon us in the short time we were there. Because of their leaning toward pop rather than rock, the ambience, dynamics and overall production at Crescent left us with a final product that sounded (in a positive way) different to other NWOBHM fare at the time. All of the songs were recorded live, the vast majority being first takes; we didn’t have the luxury of prolonged hours spent multi-tracking and ‘tidying’ and as a result there is a refreshing rawness and spontaneity in these recordings, a feeling of being ‘in the moment’ reminiscent of Led Zeppelin's first album. It was a live performance in a controlled environment; there are flaws, but these do not make the end result any less impressive.

Our songs, like the band, were evolving constantly from blues to twelve bar, from progressive rock to rock standards (well, almost!) but everything we did was fused with an aggression born out of our self-confidence as individual musicians and arrogance as a band. With ‘Bounty Hunter’, the earliest song in this collection, the balance seems to err on the side of aggression with the most basic of riffs and a lyric devoid of fantasy and fairy tale. ‘Pride Before A Fall’, ‘Drunken Women’ and ‘Battle Of The Eve’ followed with the Moog Taurus foot synthesiser featuring heavily. Although the songs were composed before the expensive Moog was attainable, they were always written with it in mind. ‘Pride Before A Fall’ was an obvious single whereas the other two were ‘assembled’ lengthy pieces of music incorporating different time signatures and syncopated rhythms which always impressed the musos but sometimes left the average punter a bit confused at gigs!

Nick and I got on unbelievably well musically. We were at the top of our game and could anticipate each other’s every move, and with no restraints in that environment we flourished. The songs began to lean heavily toward the rhythm section taking centre stage, the guitar being used to embellish, which was not a conscious decision but as it happened at that point in our development turned out to be a refreshingly different by-product that enabled us to explore other paths we might never have gone down. This approach formed the basis of the songs that followed, ‘Still Comin’ Home’, ‘After Battle’ and ‘Confusion’, with the addition in the latter two of the Moog Prodigy keyboard. The right length, a nice hook and a blisteringly good riff, ‘Still Comin’ Home’, as with ‘Pride Before A Fall’, had ‘single’ written all over it. ‘After Battle’ was the second part of the ‘Battle Of The Eve’ opus, following a similar path to its predecessor but overall was a little more polished. ‘Confusion’ was just that! An all-out attack on ‘the norm’, every sequence throughout is subtlety different to the last. And with no chorus and no guitar solo for a hard rock band this was unthinkable, but we were pushing boundaries and ultimately it’s up to the listener to gauge whether we got it right or not.

From the sublime to the ridiculous, originally used as an instrumental framework to facilitate Nick’s drum solo ‘Hancox Half Hour’ ‘If It Takes A Man A Week To Walk A Fortnight Then How Long Is A Piece Of String’ was, at just 2.44 long a conscious step in a different direction – short songs with long names. The title had no bearing on Paul’s lyric, which was a ditty about us as a band, where we were and where we thought we deserved to be. It was crammed with clever little passages, manic riffs and hooks. The song was recorded both at Crescent and then again at S.A.M. mainly because we felt we didn’t do it justice at Crescent the first time around. Listening retrospectively I’m not sure now which version I prefer, although unfortunately only the S.A.M. version of this track is represented on this album as the Crescent recording couldn’t be restored to an acceptable standard. ‘In The State In The City’ was also recorded at S.A.M. Studios in Bristol (incidentally engineered 35 years ago by Steve Street who remastered this collection); it was the band’s final offering, a song of commercial length which in arrangement almost followed a standard format. Personally I preferred the cleaner crisper sound that Crescent provided, but S.A.M. certainly left us with something to be proud of.

Listening to the songs now, there maybe a couple of things I would edit, but then again… As Bob said to me recently, ‘they are what they are’, and he’s right. They are a product of their time, and who am I to inflict a mature head and today’s trends on recordings made thirty-six years ago by a bunch of young dedicated musicians. And come to think of it I would probably ruin them if I did. They are perfect as they are.

This is a record of Stormtrooper spending two very productive Saturday mornings in Bath and one Sunday afternoon in Bristol, and I for one applaud its spirit, enthusiasm and not least its brilliance –if I do say so myself!

Colin ‘Boggy’ Bond, March 2016