| ||||

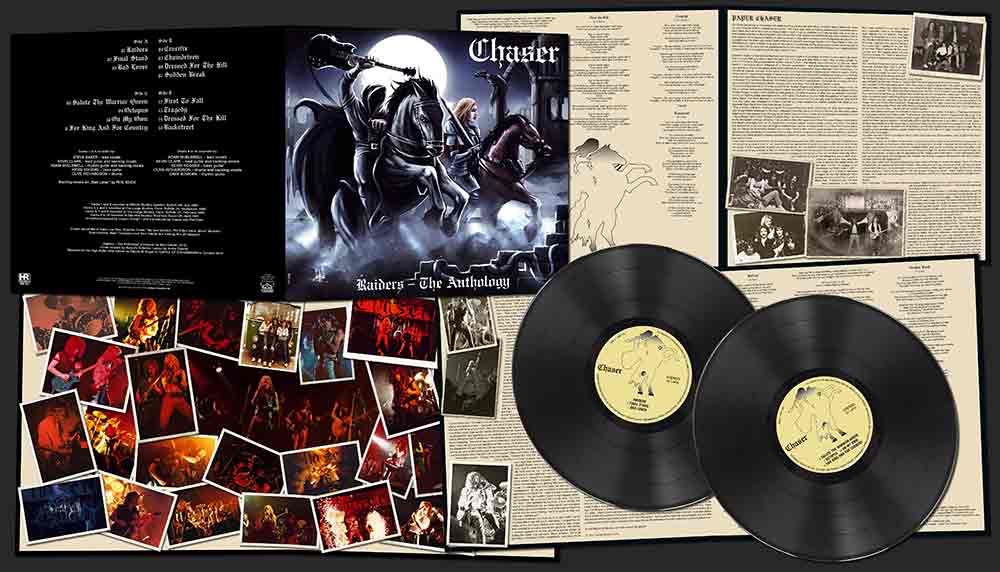

| CHASER - Raiders - The Anthology DLP | |

HRR 540, ltd 300, 150 x black + 150 x transparent electric blue vinyl, gatefold cover, 4 page insert | |

| 01 Raiders 02 Final Stand 03 Bad Lover 04 Crucifix 05 Chaindriven 06 Dressed for the Kill 07 Sudden Break 08 Salute the Warrior Queen 09 Octopus 10 On My Own 11 For King and for Country 12 First to Fall 13 Tragedy 14 Dressed for the Kill 15 Backstreet | |

SOLD OUT! | |

remastered and specially mastered for vinyl by Patrick W. Engel at Temple of Disharmony

For those too young to remember, it’s worth pointing out that the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal was really no more than an artifice created by journalists. Few if any acts went out calling themselves a NWOBHM band back then; they were hard rock or heavy metal or rock ‘n’ roll or whatever, and that was that. And, to be fair, a point made recently by Stormtrooper’s Colin Bond that in his opinion the NWOBHM was more a period of time than a genre has a degree of validity. In the course of our discussion Chaser’s Clive Richardson would point out several times that they were never a NWOBHM band, yet their sole single ‘Raiders’ b/w ‘Final Stand’ is about as NWOBHM as it gets in terms of its sound, its style and its attitude. As the elusive record deal remained out of their reach like so many of their contemporaries in the glory days of the NWOBHM Chaser went ahead and did it themselves, and a damn good job they made of it too.

Chaser’s legacy is founded on that one highly-prized single and a number of sessions recorded in the hope that a single A&R guy would wash the dust out of his ears and offer them a deal. They received almost no column inches in the press outside of their native Suffolk – the county once referred to by Sounds’ Geoff Barton in an article about Trespass as a “bucolic backwater” – and even the ever-reliable Malc Macmillan had precious little to say about them in his NWOBHM Encyclopedia. Even drummer Clive Richardson, not himself an original member of the band, had to do some homework to bone up on Chaser’s origins. Still at school (and in the crowd a couple of times) in Ipswich when they took their first tentative steps around Suffolk under the name Stormchild – not to be confused with the lads from Lancashire, nor the band who contributed ‘Holocaust City’ to Ebony Records’ ‘The Metal Collection Vol.2’ compilation – Clive was an outsider when the band changed their name to Chaser, a move which took them from the generic to the unique.

“Stormchild was formed in 1979 by bassist Kevin ‘Bodge’ Rogers and guitarist Gary Smith,” begins Clive. “At that time they were predominantly a covers’ band. Gary left shortly after to join fellow Ipswich-based rockers Woden Forge, so Kevin Clark joined as lead guitarist and after a couple of other line-up changes, Phil Eden joined on rhythm guitar and lead vocals, with Adrian Scofield on drums. With the addition of lead vocalist Steve Baker, the band decided to concentrate on writing and performing only original material, and at that time the name was changed to Chaser. Phil left and was replaced by rhythm guitarist Nik Wilding, and drummer Paul Read took over from Adrian Scofield.

“This is where I came in. I’m the youngest, the baby of the band, and I joined them in 1982, and the following year Shag [Adam Shelswell to his mum, although Clive later mentions with a smile that “he was never called Adam at all; he’s always been Shaggy to us”"> took over on rhythm guitar. And that became our stable line-up – Steve Baker, Kevin Clark, Bodge, me and Shag – for the next three years or so.”

As for the band’s change of name, “I’ve spoken to the other guys about how the name Chaser came about and here’s what they told me. As Stormchild, the band played predominantly covers, and when they made the decision to write and play all original material they wanted a different identity to lose the ‘covers’ band’ tag, so Chaser (as in whiskey chaser) was chosen. There is also a link to steeplechase too, which is why the band used the character on horseback as the logo. Bit of a loose connection, I know, but there you go! Incidentally, two other possible names considered at the time were Triton and Warrior apparently, but Chaser got the majority vote.

“I was still at school when I first came across them because I was only sixteen when I joined. I’d literally just left school to pursue a rock ‘n’ roll career if you like, and at the time my mum was quite friendly with Steve, the singer. I don’t remember exactly how it came about, but she told him one day ‘my son’s a drummer’ and he happened to say something like ‘oh, we’re not very happy with the drummer that we’ve got at the moment; would he be interested in coming up and trying out for us?’ So that’s basically what I did. I went up to one of their rehearsals, got on their drummer’s kit, did a little solo, and they kind of sacked him pretty much on the spot, I think!” he laughs. “A bit mercenary, but that’s rock ‘n’ roll!”

The image of a cocksure teenager swaggering into the rehearsal room springs to mind, but Clive is quick to refute that. “I wouldn’t say I’ve ever been cocksure, to be honest. But I was confident in my own abilities, and I suppose I was an ambitious teenager, heavily into Iron Maiden; they were always my favourite band, and I was heavily into the NWOBHM kind of style. As a drummer, I had my own personal heroes, drummers that I wanted to be like, but at the time Chaser were by far the most popular and the biggest band around this kind of area. So I kind of left school and walked straight into the dream job, really.”

The fact that Richardson senior was a drummer ensured that Clive knew his way around a kit. “My dad was a big band swing drummer, so I was brought up with the likes of Art Blakey and Jack Parnell being played around the house. Cozy Powell was probably my first real influence. ‘Dance With The Devil’ was one of the very first singles I bought; I think I was about seven when that came out! But as far as the rock players go, Neil Peart was always a major influence, I loved his style, and I liked Clive Burr; he was a great drummer, sadly missed.” He pauses for a moment. “Oh, there’s so many drummers I like that I can’t actually think of any at the moment!”

The newly-cemented line-up of Chaser was a melting pot of contemporary influences. “Steve, the singer, when I joined he used to play Foghat a lot, so I would say his influences were in that classic rock style; Bodge was a huge Ozzy fan, massive Ozzy fan, so he was from the Sabbath and Seventies rock and metal end of things; Kev used to love Wishbone Ash, Shag was a big AC/DC fan, and I was more from the NWOBHM, as well as bands like Judas Priest and UFO. But to be honest, we all liked a bit of everything. I was a huge Abba fan as well. I love Blondie… We all had very eclectic tastes.”

In July 1984 Chaser ventured into Hillside Studios in Ipswich to record their first demo. “That was the first time for that particular line-up in the studio. That was the first session that me and Shag did with the guys.” The fruit of their labours would turn out to be their single, although Clive is quick to point out that, technically, that came from their second session. “We actually went in slightly before then to do a demo – a four-track demo – so there are actually another two songs but we haven’t been able to track down the masters of those. But then we went back in to remix ‘Raiders’ and ‘Final Stand’, and it’s the remixes that made it onto the single. We did actually spend probably another couple of days remixing it, and I think I’m right in saying that Kev did some of his guitar parts again.”

The other two tracks from the original session that have been lost, Clive confirms, were ‘Light Of The Night’ and ‘Riot In The Streets’.

“It had always been an ambition for the band, obviously, like all the other bands of the time, to get a deal,” he continues. “We did contact quite a few labels but we were kind of, well, it seemed like we were stuck in the middle: most labels, the sort of more pop-orientated labels, said ‘you’re too heavy’ and then the other more rock (in inverted commas) labels said we weren’t heavy enough. So we said, ‘sod this, we’ll put a single out. We’ll do it ourselves.’ So that’s why we decided to go for ‘Raiders’ and ‘Final Stand’, it was a democratic decision by the whole band, and we figured that ‘Raiders’ was always a popular live song and was also probably the most commercial thing we had.

“It went down really well. We got a thousand pressed, and on the launch where we played, I think, The Grand in Felixstowe, we seemed to sell loads of them – the place was rammed, which was great, and we sold quite a lot on that first night; everyone was coming up and wanting them signed and things. By the end we were all moaning about having to sign them! It felt like we were doing it for hours – which is great, really; let’s be honest – so I really feel for these guys like Robbie Williams who have to sign hundreds and hundreds of promos posters.”

Really?

“No!” he laughs. “I’ll take that back! But at subsequent gigs we sold them from the ‘box in the corner’ – merch stand is probably too grand a name for it – and we always managed to shift quite a few of them.”

However, the release of ‘Raiders’ in 1984 didn’t translate into either massive national press adulation or interest from the labels, so the following year they decided to try again. “It was a constant ambition for the band really to get that deal. We were ambitious but obviously not ambitious enough. Or maybe we were ambitious enough but we just didn’t get the breaks. If we’d have been a London band I’m sure we would have probably had a lot more success. Like you said yourself, this part of the country was a little bit like the arsehole end of nowhere really, not to put too fine a point on it!”

The obvious question is to ask whether the guys ever thought of chucking everything in and moving to London. “I’d have done that at the drop of a hat,” replies Clive, emphatically. “But I was the young one and probably had a lot less commitments. Steve, for example, was married and had a young daughter at that point, I think, and he was the eldest, the elder statesman of the band, ten years older than me. It was a long time ago and I can’t speak for the others, but I would have done anything to have made it my career at that point. I was working in a factory at the time and I hated it, absolutely hated it; in fact, I think we all probably hated our jobs, to be honest. But it just didn’t happen, for whatever reason. It needs everybody to be on the same songsheet for it to happen, for everybody to say ‘OK, we’ll take the plunge and do this.’ It’s a hell of a leap of faith, and in hindsight maybe I think that the individual levels of ambition might not have been the same for all of us. Collectively, the dream was the same, but having the wherewithal to make changes in our personal lives to make that happen was probably not quite so achievable for some of us. I’d never point the finger of blame at anybody but – and I’m only speculating here, really – I think maybe there were other things going on in people’s lives that were or had to be their priorities.”

So September 1985 saw them in The Lodge in Suffolk, the studios owned by The Enid (“Robert John Godfrey is a lovely chap,” Clive recalls) for another session which saw three songs put to tape – ‘Bad Lover’, ‘Chaindriven’ and ‘Crucifix’. The session marked a change in the band, in that more songwriters were coming to the fore. “Kev wrote both ‘Raiders’ and ‘Final Stand’,” recalls Clive, “but, ‘Bad Lover’ was written by Shag and Kev, ‘Crucifix’ was mine and ‘Chaindriven’ was an instrumental by Kev; so those particular tracks were more band-orientated; there was more writing coming from other members of the band. Once myself and Shag were settled in we started contributing. I’ve always written anyway which, I guess, is quite strange for a drummer, but I’ve always been so fascinated by the whole process of writing and recording. But anyway, ‘Bad Lover’, ‘Chaindriven and ‘Crucifix’ saw more of that line-up having influence over the writing side of things.

“Out of those three tracks ‘Bad Lover’ was probably one of the most commercial sounding songs that we’ve done. To this day I think it’s the most radio friendly. ‘Crucifix’ is much more of an album track; very Maiden, one of these long, epic eight-minute songs. There’s a couple of those on this album, both mine, I’m afraid!” – another laugh – “because that was the kind of thing I loved. As I said, I was a massive Iron Maiden fan, and ‘Phantom Of The Opera’ is for me the best metal track of all time. And obviously, when I write, or when I wrote then, I loved the idea of having time changes, different rhythms, twin harmonies, guitar solos and a story as well. ‘Crucifix’ went on to become a firm crowd favourite. Once we’d recorded it and it had made its way into the set, despite the fact that it’s quite an involved song for whatever reason people loved it. ‘Bad Lover’ was a popular one, too. And the instrumentals… We did quite a lot of instrumentals which always seemed to go down well. If you listen to them you might hear a little kind of folk, sort of almost Irish jig, a tiny little bit of that influence, and people seemed to like that.”

At that time the band didn’t let the lack of A&R interest get them down. Clive recalls that they were probably all a bit jaded at times, “but we were busy. The main thing we used to do was bike rallies; we used to do hundreds of those, all over the place, God knows where… Generally they were in the middle of nowhere, in the middle of a field somewhere, and we used to do a lot of them. We used to play quite regularly at the Corn Exchange in Ipswich too. That was one of the bigger gigs we did. But the thing was that we never earned any money from the band at all. Any time we got paid for any gigs that we did, and there was never that much money because there were always overheads and expenses to come first, the remainder was ploughed straight back into studio funds because we all loved recording. That was a real passion of the band, and why we ended up making all these recordings. At the time it was like ‘why are we spending all this money on studio time?’ but I’m really glad we did now. Between the September ’85 and February ’86 sessions we must have done a lot of gigs because we wouldn’t have been able to go back to the studio quite so quickly if we hadn’t had the money.”

Just five months after their first visit to The Lodge Chaser were back in the sound room once more for another three-track session. “These were new songs. ‘Dressed For The Kill’ was myself and Kev collaborating, ‘Salute The Warrior Queen’ is about Joan of Arc – that’s the eight-minute epic from that session; mine again, I’m afraid! – and ‘Sudden Break’ was another of Kev’s. I do remember that I had flu when we did that session and it was really hard work for me. I did all my drum parts and left; unusually for me I didn’t sit in on the mix at all. I just didn’t feel up to it.” Despite the quality of the material though Clive recalls that the response was “just more of the same: sending tapes out, getting little response… I think it was roundabout that time when we said we needed management. So we got ourselves a manager and we passed everything to him – mailing out to the labels, blah-blah-blah – but he couldn’t make things happen either, unfortunately. We could pull the crowds, but…”he trails off. “And I think probably at that time, this is ’85/’86, the end of the NWOBHM era, so many bands had appeared and there were a lot of bands coming through and getting signed and we were thinking, ‘we’re as good as they are; why them and not us?’”

The band recorded one final demo in April 1987, but by this time Steve had left which, inevitably, changed the dynamic within the band. Rather than recruit a new singer, they decided to recruit a new rhythm guitarist. “We drafted in another guitarist to do the recording and he ended up joining the band; that was Dave ‘Bock’ Bowden. We’ve all got these nicknames! [Clive, incidentally, was Jivs."> So he was the rhythm guitarist for those recordings. Meanwhile, Shag moved onto lead vocals. Shag always did backing vocals anyway, so he did the lead vocals on those seven tracks which also featured a re-recording of one of the 1986 songs, ‘Dressed For The Kill’.

“Shag’s singing style was very different to Steve’s. Steve was more into the classic rock kind of style, whereas Shag was more, well, as I mentioned, he was a big AC/DC fan, so his vocal style was more in the upper range, whereas Steve’s singing style was perhaps a bit more laid back, maybe.

“But as you said, the dynamic of the band changed after Steve left; it wasn’t the same, I have to say. I don’t think there was any noticeable fan drop-off, we still pulled people and still had blinding gigs. I’m not sure Shag was totally comfortable, though. I think he may have found Steve quite a hard act to follow. I wouldn’t want to upset him, but I think he’d be happy to admit that. I think they were quite big shoes to fill. Image-wise Steve looked great, and he was very cool, and I think a lot of people liked that.

“But I think it probably got to the point where we kind of realised we’d taken it as far as it could go. I do vaguely remember us having conversations like ‘this has been going on long enough now and we’re not getting anywhere; should we knock it on the head and quit while we’re where we are’ rather than getting to the point where we were flogging a dead horse. I think there comes a point where, well…” He looks for the right way of putting it. “I know at the time, and I can’t speak for the other guys, but being ambitious and wanting the band, so desperately wanting the band, to get somewhere and not achieving that, I can remember thinking to myself ‘maybe I’m not in the right band’. And I think maybe a couple of the other guys were possibly thinking the same by then. Maybe we were all sort of thinking that to get somewhere in this rock ‘n’ roll game we might have to do it elsewhere. It wasn’t that long after the 1987 session that we broke up. And obviously nothing else got released.”

Clive admits that as a band they never attempted to move with the times – don’t forget, the band’s lifespan ran through the NWOBHM years to the softer, AOR US sound that was in vogue for a while and then to the growth of thrash.

“That was the thing about us; that was what we never did. We just did what we wanted to do. We never tried to fit in with any kind of style. We didn’t see ourselves as a NWOBHM band, we didn’t see ourselves as that at all. It’s only recently that we’ve been tagged with that name. We never went out or billed ourselves as New Wave Of British Heavy Metal, and I think to be honest at the height of the band’s popularity we were kind of towards the tail end the movement, really. Maiden, Def Leppard and Saxon were like the standard bearers for it all, weren’t they, and we never really went out to emulate them, or anybody else, come to that. We were just a bunch of five guys getting together to make music and go out and play it. We were obviously a rock band, because we made a lot of noise!” he laughs. “But we didn’t want to be jumping on any bandwagons. I guess if it had been down to me I would definitely have said ‘yes, let’s jump on the NWOBHM’ because I was a Maiden freak, but that might not have sat too well with some of the other guys who were into the more classic rock side. I don’t remember anyone really putting forward any strong opinions on what direction we should go in; we just went along as we were. And that was the great thing about Chaser, we always just did what we wanted to do; we never did something just because someone said we should, and this is why to our detriment at the time we never got signed. Labels would say ‘you should be doing this, you should be more heavy’ and we were like ‘well, we’re as heavy as we want to be.’ So because we kind of stuck to our guns, we lost out.”

But in doing so at least the band kept their integrity. “Absolutely! And that was very important to us, because we were what we were. As I’ve said, any of the stuff that I wrote you’ll be able to hear a very strong Maiden influence in there, because I was very into them at the time; it wasn’t that I went out of my way to copy them or anything but that was the style that I really liked with a lot of twin guitar. But then you can say the same about Thin Lizzy as well because they were a major influence on the overall Chaser sound too. We worked at it hard for several years, and they were great years. We had good, fun times. Headlining the Corn Exchange, which holds 900, that was great, and we did a few headlining dates there actually. That was an achievement for the band. I wish I could say that we did Reading, or Donington, or places like that, but we didn’t; it just didn’t come about. But we still had a great time. And getting the single out, that was quite an achievement too; and the fact that people are still interested in it over 30 years later is quite staggering. We’re all over the moon that after all this time we’ve been signed and actually managed to get all of our recordings released by a label, and we’re very grateful to Bart Gabriel at Skol Records for his support and for making this album happen.

“And personally,” he continues, “I learned so much. I developed massively as a drummer. It pushed me. As I said, I was only 16 and I didn’t have a clue what I was doing when I joined the band, and I’d never done any proper recording. We all learned about recording techniques and we worked really, really well in the studio; we got it off to a fine art. By the ’87 recordings we really knew what we were doing, and that’s something to be pleased about.

“And we very, very, very rarely had a bad gig. Obviously there were the occasions where we were playing out of town and we even had to let the dog in free, but for the most part gigs were very well attended and we all had a blast. It was a very good atmosphere and everybody loved it, including the band. Someone mentioned a while ago that Bodge is known locally as ‘Bodge Rock Star’ – not that he never actually became a rock star,” Clive chuckles – “but it’s because whenever we played, whether it was in a small pub or in a tent in a field at a bike rally in the middle of nowhere, or wherever, he always played like he was playing Wembley Stadium; he always pulled the shapes and he absolutely loved it and from that aspect, the visual element, he was probably the one that people used to watch most, because of his stage antics. We entertained people, and we enjoyed ourselves too.”

And at the end of the day, isn’t that what it’s all about?

© John Tucker October 2016