| ||||

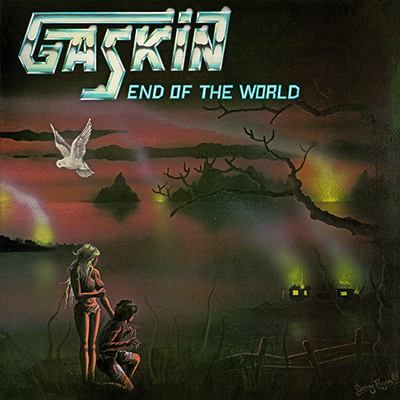

| GASKIN - End of the World LP | |

HRR 614, ltd 500, 200 x black + 300 x transparent electric blue vinyl, gatefold cover | |

| Paul Gaskin - Vocals, Guitars Stef Prokopczuk (R.I.P. 2008) - Bass Dave Norman - Drums | |

| 01 Sweet Dream Maker 02 Victim of the City 03 Despiser 04 Burning Alive 05 The Day Thou Gavest Lord Hath Ended 06 End of the World 07 On My Way 08 Lonely Man 09 I'm No Fool 10 Handful of Reasons | |

SOLD OUT! | |

mastered for vinyl by Patrick W. Engel at Temple of Disharmony

These Foolish Things

“I was sat it a flat in Clapham in South London in 1979 nursing a fractured right hand,” recalls guitarist/vocalist Paul Gaskin. “I could hardly move it. I’m sat on a cushion with a telecaster in my hand (not even plugged in) strumming up and down. In my head, there was a Marshall stack playing…”

“So I’m coming home from work,” adds drummer Dave Norman, “and Paul plays this riff to me, and asks me what I think of it.”

“‘It’s shit,’ he said!” is how Paul remembers it. “And that was ‘I’m No Fool’! To be fair, it did sound much better less than a year later!”

Issued in April 1981 on Rondelet Records, Gaskin’s first release ‘I’m No Fool’ b/w ‘Sweet Dream Maker’ was lifted straight from a four-song demo recorded in May 1980 after Paul and Dave had returned home from their stint in London. “At the end of the session, engineer Roy Neave suggested we get in touch with Rondolet Records; he had recorded Witchfynde’s first album ‘Give ’Em Hell’ for them only weeks previously and thought they might be interested,” says Dave. The band’s original plan had been to move back to London once more, and so the rhythm section went to scout things out while Paul stayed behind, and dropped in on Rondelet. And although the label were keen to sign the band immediately, and although Gaskin held off for a while in case another offer landed on the table, the rest is pretty much history, as they say.

But we’re getting a bit ahead of ourselves here. Paul Gaskin started singing in bands in 1973 at the tender age of fifteen. “We were called Praying Mantis at first at my suggestion,” he recalls, “but only lasted one gig. Then we started going through names… Titus, Freedom Fallacy, and lastly Firebird. I wasn't impressed with our axeman, so took it up myself. One day there was a knock at the door, and there stood David Screen. I’d only just started playing guitar, but he said ‘I want to start a band; I’ve got a friend who’s a drummer, and I play guitar but I’m going to go onto bass because I hear you’re a guitarist,’ and at the time, to be honest, he was far better than me. I was rubbish! Anyway, we used to practise in this garage at Rampton Hospital where his dad was the medical boss, and I started writing rock songs, rather badly, and very Kiss-like early on. We did several little gigs and it kind of faded out. But that was Ripper, my first band as a guitarist.”

Meanwhile, around the same time, 1976 to 1978, some 30 miles away from Paul’s stomping ground in North Nottinghamshire, Dave Norman was also starting out in what he calls “a series of covers and originals bands: High Tension (I still have a dodgy recording of our second gig, recorded at the Chicken Hut in Scunthorpe where Paul and I had our first jam and where Gaskin ended up rehearsing there for the first two-to-three years); Record Player, which included Martin Fish and Douglas Madden-Nadeau, a local guitar hero; Steel Tear; and then Vibes Macabre, with Doug on guitar and Stef Prokopczuk on bass.”

Paul takes up the story. “Sometime early 1979, I got a call from a Martin Fish. He lived in Scunthorpe, and Baggy told him I played guitar.” (As an aside, Baggy, or Mark Carlos Imonts Lagzdins, was an old friend of Paul’s and was, as Dave recalls him, “a local character on the Scunthorpe scene. He was looked up to as a sort of Fonz godfather biker figure, I guess, and had been a bass player in a lot of bands in the early Seventies… I’ve no idea where the name Baggy came from, but certainly at that time if you mentioned his name, practically everyone in town knew who he was.” He would later join Gaskin for their second album ‘No Way Out’.)

“We met in a pub called The Priory [which would go on to become the band’s spiritual home">,” continues Paul, “and Martin introduced me to his drummer. Shallow as young people are, I didn’t think he looked the part. But then Dave Norman walked in and he did look the part, and I got Martin to arrange a jam. We played all the way through ‘2112’, and it was instant bromance!”

“I think we first met in March or April 1979, something like that,” adds Dave. “I wasn’t happy with Vibes Macabre; I didn’t feel that the songs were good enough to take the band anywhere, so whilst not actively looking, I was in the market for a change. Paul had hooked up with Martin, another Scunthorpe bass player I’d previously been in a band with, and one night they were sat in The Priory having a beer after a bedroom rehearsal and I walked in, all camel-coloured duffel coat and long hair. According to Paul, Martin pointed at me and said ‘he’s a drummer’, and Paul replied, ‘yes, OUR drummer!’ Maybe it was the duffel coat!” he laughs. “Anyway, we chatted, I agreed to join them for a rehearsal, at which, if memory serves, Paul and I romped through Rush’s ‘2112’ – all of it – with Martin struggling to keep up, plus Ted Nugent’s ‘Cat Scratch Fever’, Van Halen’s ‘Running With The Devil’, maybe a Montrose song, a few other covers, and also went through the bones of what became ‘Burning Alive’, ‘Despiser’, ‘Sweet Dream Maker’ and maybe ‘End Of The World’. I had previously worked with around half-a-dozen guitar players in various line-ups – I was just about to turn 20 – and Paul was light years ahead of the guys I’d played with previously. Not just in terms of technical proficiency, but feel, songwriting awareness, everything. We clicked both musically and as friends immediately, so I jumped ship and we set about rehearsing in earnest. The writing relationship at that point was that Paul came up with all the riffs, choruses, pretty much all the lyrics, and I had an ear for arranging, sequencing the sections of a particular song, adding some time signature quirkiness, tempos, that kind of thing.”

“My song writing was improving,” agrees Paul, “and I was writing in set order. I started off with ‘Burning Alive’ which I had started with Screeny, then ‘Sweet Dream Maker’, ‘End Of The World’, ‘Despiser’, and so on. We realised that Martin wasn’t keeping up, so decided to get a new bass player. At this point we had decided on Sceptre as a name. Dave moved to London, and persuaded me to join him, so we spent three or four months in late ’79 there. We also checked out the competition at the Ruskin Arms: Iron Maiden, Angel Witch etc. But I hated London, so we decided at Christmas 1979 to come home.”

“Following that first jam and the early rehearsals during mid-1979… Well,” Dave starts again, “the initial motivation for moving to London around August 1979 was because I was going through a break-up with my then girlfriend, Penny. Why is there always a girl involved?” he ponders. “Anyway, we’d decided to make a fresh start in the Big City, but her rather Victorian Dad had decided that I must go first, find somewhere to live, and get a job! So that was the main motivation. Plus, of course, the thought of our chances of doing something meaningful musically would be much greater in London. Long story short, Penny never did join me! But Paul did, so the bromance outlived the romance!” He laughs again at the memory.

“I initially stayed in digs with my old musical buddy, Doug Madden-Nadeau and his girlfriend, in Bayswater, but then when I convinced Paul to join me we moved into his cousin’s empty flat in Clapham, South London. We both had various day jobs to pay our way, but tried many times, unsuccessfully, to recruit a bass player. We’d left Martin behind in Scunthorpe; as Paul says, as nice a chap as he was, it was obvious he wasn’t going to be able to keep up with the musical standard we were trying to achieve. We almost auditioned a bass player called Nic Simper, THE Nic Simper, the original bass player with Deep Purple; Paul met up with him in Acton where he was working, but I guess we were too young and green by his standards.

“Ultimately, the reason that it didn’t work in London was a combination of not being able to find a bass player – which sounds ridiculous forty years on, but we were only 21 and 20 years old at the time – struggling financially, and some degree of homesickness. Paul’s relationship with his then long-time girlfriend also didn’t survive the rift of us going to London. I often wonder what would have happened had we stayed. Unlike Paul, I loved London, and could see that there were a lot of opportunities there for us.”

For any struggling young bands, that might well have been the end, but Paul and Dave’s friendship gave them one last throw of the dice. “Early January 1980 I took David to an audition in Bristol,” Paul recalls. “It was freezing, and we slept in the car overnight. Good as the band were, on the way home Dave said we should keep trying.”

“I can’t recall the exact date or sequence,” admits Dave, “but as Paul says, it must have been early January. We weren’t sure if we were going to continue, as we didn’t have a bass player at the time, so immediately after Christmas 1979 I replied to an advert in the Melody Maker, and Paul kindly took me to the rehearsal. It was actually in a little village called Box, near Bath, and the band eventually became Bronz. They had a more AOR slant and released a couple of albums with Max Bacon on vocals a few years later, though he wasn’t with them at the time. It was just guitar, bass and drums. The guitarist, Chris Goulstone, was phenomenal. The sound was somewhere close to the Pat Travers band at the time, I guess. I was offered the gig, but turned it down, mainly because of the isolation of where the band were based – I couldn’t drive at the time – plus I also thought that Paul had stronger material, if we could just find that elusive third band member.”

“Having made his decision, on the way home Dave also suggested we change the name to Gaskin,” says Paul. “I was mortified. I thought it was a rubbish name. But having quoted Van Halen, Santana, Montrose, et al, he convinced me. Then he rang me one night that same month to say he'd found an old pal who played bass. Rehearsals ensued, and away we went.”

“As Paul says, on the way home (we had to stop because of freezing fog – you could only see about 20 feet ahead!) I punted the idea of calling the band Gaskin – influenced by Montrose, Santana, Van Halen etc,” acknowledges Dave. “Possibly it didn’t have the same ring as all of those, but my idea was that we were less likely to be pigeonholed as ‘one thing’ or ‘one sound’. I’ll freely concede now that Iron Maiden, Judas Priest and Metallica and many others have done very well with a clearly defined name and brand, but we were young! I think the next day I got a call from Doug Madden-Nadeau saying he’d also returned from London, pleading poverty, and asking me what was I doing. We rehearsed with Doug on bass a few times, but it didn’t gel too well, and Doug was clearly a frustrated guitarist; you could sense there would be trouble ahead! Then came a chance meeting with Stef Prokopczuk in a pub, a trip to the Chicken Hut for a jam, and all the pieces were in place.”

Paul’s archive reveals that the first official gig Gaskin played was at the Retford Porterhouse on 8 March 1980 supporting The Planets. “But we got a gig the night before at the Nelthorpe Arms in South Ferriby to warm up. I’m sure the Nelthorpe gig would’ve been sponged out with cover songs, but the first set at the Porterhouse was ‘Burning Alive’ / ‘Sweet Dream Maker’ / ‘Despiser’ / ‘Lonely Man’ / ‘End Of The World’ / ‘Lay Me Easy’ / ‘Don’t Worry ’Bout A Thing’ with the never recorded ‘Heading For The Skies’ closing the set.”

With a settled line-up and a growing catalogue of material, the band decided to record a demo and opted to go to Fairview Studios in Hull. In one eight or ten hour session (time dims the memory) on Saturday 17 May Paul, Dave and Stef committed ‘Despiser’, ‘End Of The World’, ‘I’m No Fool’ and ‘Sweet Dream Maker’ to tape.

“It was a very memorable day, for the wrong reasons at the start,” recalls Paul. “A friend of Stef’s had promised us a lift to the studio (this was before the Humber Bridge was opened), but let us down at the last minute, so we scrambled to get a hire van. Then when we got onto the motorway it broke down. We managed to get hold of the company – how I’m not sure now as, of course, we didn’t have mobile phones then – but they got us a replacement and we transferred the gear across. That made us an hour late for the session, but we still managed to get four tracks recorded and mixed in eight to ten hours. Dave remembers me doing the solo of ‘End Of The World’ without it being in my headphones, as I didn’t realise that Roy Neave was recording: so the solo you hear is me doodling along regardless. I remember the smell of the place too. I recently took a friend of mine from Texas over there, and it was the first time I’d been back since 1981, and the first thing that hit me was the smell. A kind of electrical charged dust smell. It brought it all back. I learned the art of double tracking my voice then too. I didn’t have a very strong rock voice, so Roy suggested double tracking and I loved it. At the end of the session Roy suggested we get in touch with Rondolet, and I took the tape over to them two days later, and was offered a deal.”

“As well as the stress of breaking down en route, I too remember the smell of Fairview,” adds Dave in agreement. “I always loved that place. I chose it as our first recording venue as Def Leppard had recorded their Bludgeon Riffola EP there and I loved their production on it – that was also done by Roy. I think because we had rehearsed those four songs quite a lot, and by then had played quite a few local gigs, we were very tight, and able to get good takes very quickly. The speed we achieved those results, as the first time in a studio, is quite remarkable, really. Because it was only an eight-track studio, we got a ‘sound’ very quickly and were able to start taking within an hour or so – very fast, really. I would love to get my hands on the original eight-track tapes, but they’re long gone. We didn’t have the foresight – or the money! – to buy the tapes, and in those days if you didn’t buy the multitrack the studio would simply re-use it. This was pre-Rondelet obviously, so we had no record company to pick up the tab, either. I think the day cost around £200, including transport.

“I was in the control room with Roy and Stef whilst Paul was overdubbing the ‘End Of The World’ solo, and he just thought it was a run-through. Roy taught me a studio trick that I still employ to this day, which is to tell ‘the Talent’ (as we say!) that you’re just trying a run-through – not recording – as this almost guarantees a more relaxed performance because the artist doesn’t get ‘red light’ syndrome!”

With the tape in the bag, plans were made for the band to relocate to London once more. “Stef and I travelled down two days later on the Monday, with Paul staying behind to tie up some loose ends. On the first day we secured a flat and jobs, delivered the demo tape to every major record label we could think of, and rang Paul to let him know. His reply was, ‘you may as well come home, I’ve been to see Rondolet in Mansfield Woodhouse and they want to sign us’.

“The offer was a two-album, two-single deal, and we returned from London with the intention of doing that. We eventually delayed on signing, because in the weeks following the demo recording, tracks from it started appearing in the Sounds HM chart, which as I’m sure you know, was compiled from popular requests at around nine or ten leading HM discos around the UK. We realised that maybe we shouldn’t just sign with the first comer, and also very soon after that, Neal Kay got in touch, and offered to mentor us, and try to secure a deal for us in the same way that he had assisted Iron Maiden. To cut a long story short, the liaison with Neal Kay eventually came to nothing, although I understand he was negotiating with Arista Records on our behalf. Early in 1981, frustrated at the lack of forward motion, we decided to sign with Rondolet who, amazingly, were still interested.”

“So the single should have come out a couple of months after the session,” says, Paul, “but we’d started hanging out with Neal Kay who persuaded us we could do better, and, much to my regret now, we listened to him. It was one of several daft mistakes we made at the time.” The single – drawn straight from the Fairview session – was pretty much ready to roll, with ‘I’m No Fool’ chosen for the A-side backed with ‘Sweet Dream Maker’ (“‘End Of The World’ had a bum note in it, and ‘Despiser’ wasn’t really single material, so it had to be those two really,” says Paul, matter-of-factly) but it would be almost a year before it saw the light of day. And when it did, it was on Rondelet anyway, the band eventually deciding to go with that original deal and signing to the label in early 1981. The band’s debut 7” was released in April 1981, and the same month saw them at Fairview once more, where they ended up with twelve songs for an album to be called ‘End Of The World’. All four demo tracks were re-recorded and made the final LP, and with too much material for the time constraints of a record back then, ‘Broken Up’ (which had been seen as a possible follow-up single) and ‘Don’t Worry ’Bout A Thing’ failed to make the final cut. (These two songs appear on the High Roller Records’ sister release ‘Beyond World’s End’.)

“Back in those days, the longer you made the album, the less wide the grooves were, and consequently, there was less bottom end,” explains Paul, “so we knew we would have to leave a couple of tracks off. ‘Broken Up’ was the newest song, having been written just before we recorded the album, and we wanted to record the older material first, and ‘Don’t Worry…’ was a little bluesier than the rest of the material, so that was a no-brainer too. And to be honest, I was actually pretty wrecked when I sang ‘Don’t Worry…’ – we had been drinking a case of Newcastle Brown, and I think you can tell when you hear it!”

“I agree with Paul,” says Dave, “in that we were trying to use the older material to frame that first album, and ‘Broken Up’ represented a bit of a change of direction for the band’s sound – I prefer the second version we did of it for [the band’s second album"> ‘No Way Out’. It’s not that either of them were weak songs; they just didn’t fit the tone of the rest of the album.”

Released in July/August 1981, ‘End Of the World’ is a strong, no-nonsense album. Dave has reservations over the mix, acknowledging that it was rushed because of technical difficulties in the studio on their tenth and final day there, and, as Paul notes, “we did the best we could at the time. We should have put our foot down a little more with Roy as he was smothering the vocals in reverb – a cardinal sin, we later discovered – and he kept saying ‘it’ll be ok in the end mix, I promise’ but it wasn’t. It had a lightweight sound to it to my ears, where I wanted ultra-hard. Still, it is what it is, and I liked Danny Flynn’s cover.”

Reviews at the time were thin on the ground, but in their ‘NWOBHM A-Z 10 Years On’ supplement Kerrang!’s Derek Oliver noted that: “their debut album ‘End Of The World’ contained a surfeit of epic rockers with long titles and even longer running times. The production, by Roy Neave, may have been primitive but it did the job nicely allowing Gaskin to massage musical areas that most of the NWOBHM had conveniently forgotten about.”

Had Gaskin been able to capitalise on the album’s release their profile could have increased immeasurably. However, as with the majority of NWOBHM bands, something was bound to go wrong sooner or later, and in Gaskin’s case it was taking advice on board about getting a frontman. In the time between recording the demo and the album, Gaskin had experimented working as a four-piece by bringing Dave Screen in as a second guitarist, but this lasted only, in Paul’s opinion, about four gigs. Now, however, the advice was to get a vocalist. Paul remained unconvinced, not seeing Gaskin as what he calls a “cock-rock band”, but eventually went with the tide. When they eventually settled on Mick Clarke, the band recorded one demo and almost immediately split in two, with the vocalist taking Stef with him to form Ace Lane. A new bassist was recruited – the self-same Baggy who’d introduced Paul to Martin Fish – and a friend of his was singer Bren Spencer. As a four-piece they’d record the band’s follow-up album ‘No Way Out’ which was released in August 1982, but the magic was beginning to seep away and by the end of that year it was all over.

Gaskin have periodically reformed over the years, releasing a two further albums ‘Stand Or Fall’ and ‘Edge Of Madness’, and High Roller Records have recently re-issued ‘Beyond World’s End’, a collection of demos and out-takes from the band’s original line-up. In addition, when Geoff Barton and Lars Ulrich compiled their ‘New Wave Of British Heavy Metal ’79 Revisited’ album Dave recalls that the Metallica drummer “specifically requested the single / demo version of ‘I’m No Fool’ for the album… I’m reliably informed as well that Metallica considered – and maybe recorded, who knows? – a version of it for ‘Garage Inc’.”

Looking back on the NWOBHM now, Paul’s view matches many of those who were there at the time. “Here’s where I get on my soap box,” he starts. “I’ve got to admit, in ’79 Dave and I both thought that there was a train leaving the station, and although we might not be in the front carriage we’d better hurry up and get on before it left. Having said that, an awful lot of people appear to regard NWOBHM as a style of music, which it most definitely wasn’t. It was a moment in time. Nothing more. Already by the time we brought out our debut album in ’81, I wondered if we’d missed the boat,” he laughs. “Sorry for mixing my metaphors!

“But it was really good fun” he continues. “We had an empty canvas, with our whole world ahead of us. Living together for a while in a flat in Nottingham was memorable, and seeing ‘Sweet Dream Maker’ in the heavy metal charts in Sounds for the first time, that was cool. Gigging with our peers, like Praying Mantis, Vardis, the EF band, and Girlschool was pretty cool too. It felt like we were taking the musical ground back off the punks and new wavers. We had a brash naivety back then which,” he admits, “I miss more than anything.”

John Tucker May 2018